Accommodation and employment were organized by GDR representatives and the embassies of the workers’ countries of origin. The migrants had no input regarding their contracts and no choice over what occupation they would be trained in. Nor was the length of their stay in the GDR determined by the requirements of the education they had been promised. When it came to negotiating intergovernmental agreements, financial and labour market considerations came first. In general, the contracts offered an employment period of between three and five years.

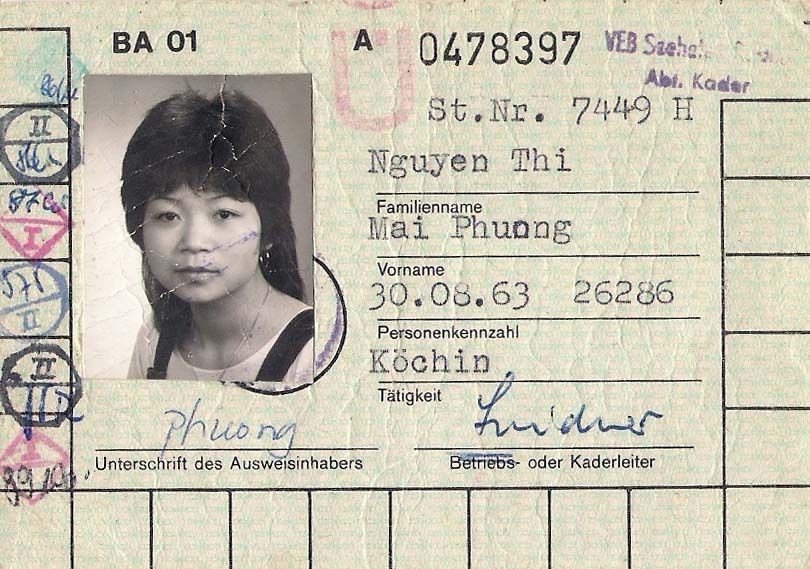

Almost 70,000 Vietnamese contract workers were employed in around 650 publicly owned enterprises (VEB). “By and large, they carry out low-skilled and menial tasks where the fluctuation rate of GDR workers is particularly high (…). Three quarters of these foreign workers do shift work.” (Feige 2011)

This was the case in the port of Rostock, for instance. Aside from kitchen work, contract workers were put to work loading and unloading ships. This was Nguyen Do Thinh’s first job in the GDR.

»It started with work in cargo handling

Nos iremos trabalhar com povo “We will work with the people” – Refrain of a song sung by Mozambican contract workers at assemblies.

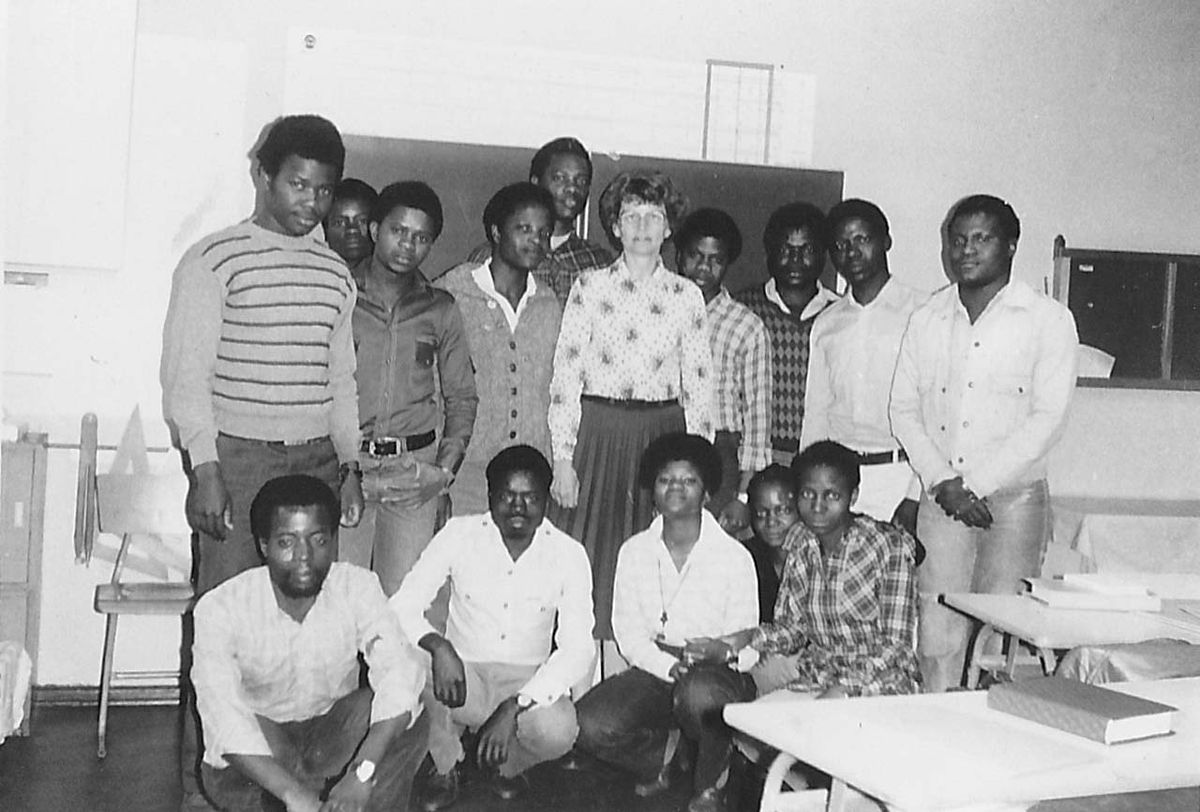

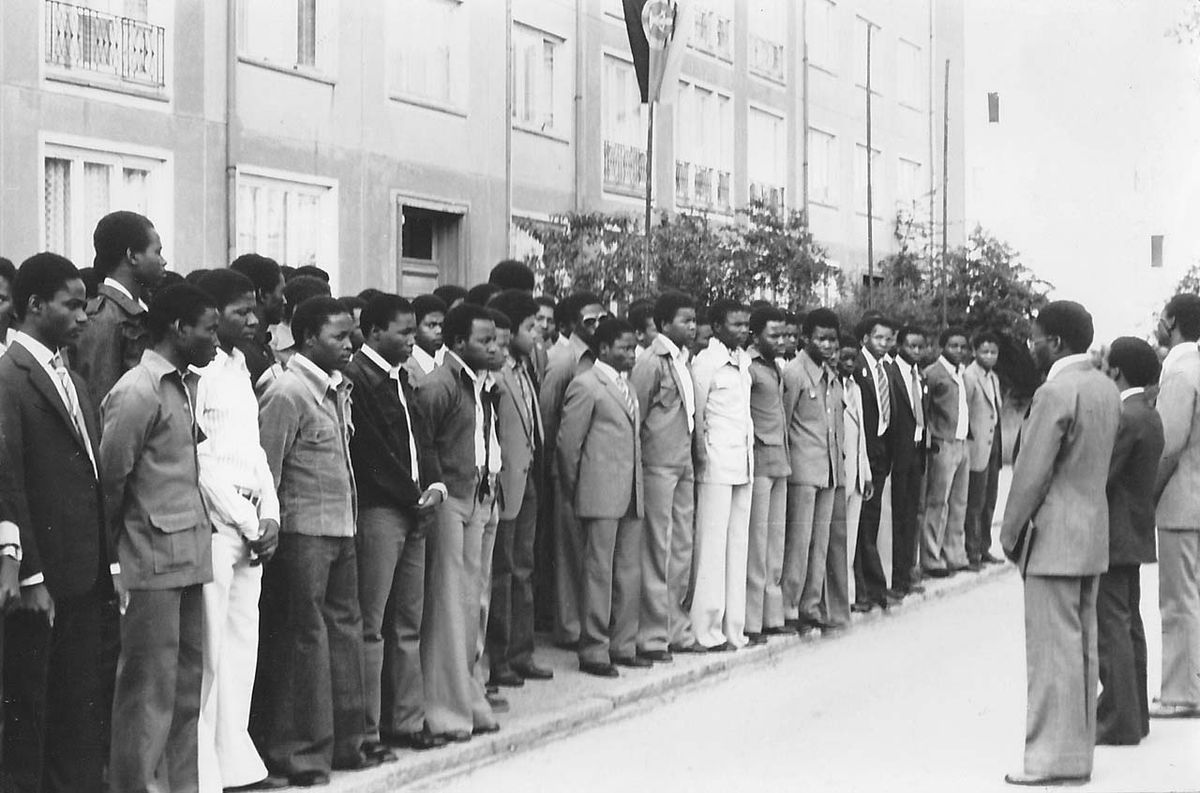

Over 20,000 young people from Mozambique arrived in Over 20,000 young people from Mozambique arrived in East Germany between 1979 and 1988. These young men and women wished to learn a profession, and some also wanted to study. In Moatize in the north of Mozambique, coal mining was expanded with the help of the GDR, with the aim of exporting it to Germany later. Skilled labour was required for this project. At the same time, there was a lack of workers in the labour-intensive coal mining industry in the Lusatian region. A film made by a collective at the VEB brown coal combine (Kombinat) in Senftenberg depicts one of the first groups of young Mozambicans being trained in the GDR coal mining industry. The collective followed this group on camera for four years.

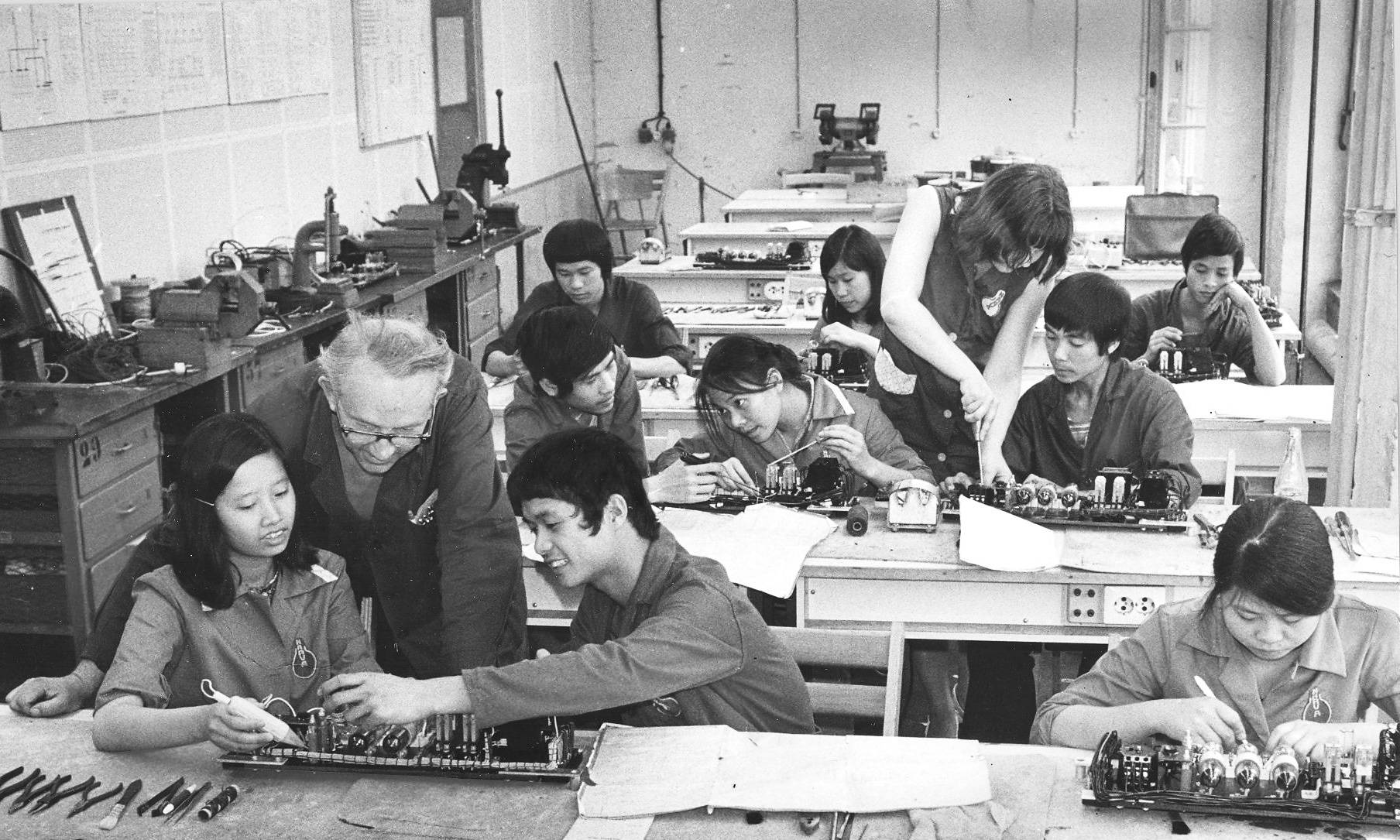

Education in the Production Process

While Mozambican contract workers did receive vocational training, they were to earn their qualification within “the production process”. Following a one-to-five-month phase of settling in and learning German, they were employed as factory workers, the idea being that vocational training would take place after hours. They mostly worked in mining, railways, agriculture, slaughterhouses, and meat processing plants.

Ibraimo Alberto

Ibraimo Alberto arrived in the GDR in 1981 aged 18. In his home country of Mozambique, he had already been working towards a career in sport, and now hoped to pursue sports studies in Germany. But he quickly realized that the officials from the State Secretariat for Labour and Wages had other plans for him, and that sport would be limited to his free time.

New arrivals were divided into groups directly at the airport; these groups were then assigned to companies. From this point onwards, the companies were basically responsible for organizing the everyday lives of contract workers. They provided migrants with accommodation and German lessons, gave them work, and were also responsible for providing them with things to do in their free time.

Ibraimo Alberto and some of his friends were assigned to the canning department of Fleischkombinat Berlin (Berlin meat processing plant). The young African men were not sure of what to expect from their new workplace. Their shock was all the greater when they visited the meat plant for the first time.

Returning to Mozambique was out of the question. The country had invested in these young people, and Mozambican officials argued that they had to repay this investment by working in the GDR. They were threatened with 15 years’ imprisonment in Mozambique if they did not. Regulations on the GDR side of the arrangement were also strict.

It was not possible for workers to change roles or end contracts prematurely of their own volition. By contrast, companies could end contracts if workers were alleged to have violated “socialist work discipline” or if they could not work for a lengthy period of time due to illness or pregnancy. While the career plans of GDR citizens were certainly subordinated to the economic plans of the government, the situation was even worse for contract workers. Officially they had equal legal status, but their residency rights were bound to an existing employment contract. Once the work contract ended, the right to residency expired.

»We stood up for ourselves

Despite the threat of disciplinary measures, Nguyen Do Thinh and a number of his colleagues refused to accept their assigned duties in the port of Rostock. As a result, he no longer had to haul sacks—but was unable to progress in terms of skills qualification. He formed a group with several colleagues and confronted company representatives and Vietnamese diplomatic representatives with demands for access to professional training.

Eventually, Nguyen Do Thinh received training as a fitter, excelling in the job to the extent that his foreman proposed he go to a master school for the trade. While the intergovernmental agreement specified that obtaining qualifications was an essential goal of worker residency, attending a master school seemed beyond of the realm of possibility. A petition for Nguyen Do Thinh was initiated by his foreman, who was also union representative for the work team. In the end, the Vietnamese Embassy consented, and allowed Nguyen Do Thinh to obtain a qualification as a master fitter.

The Vietnamese Trainee Strike

The records office of the Ministry of State Security (BStU) contains further reports of young Vietnamese migrants struggling to improve their living and working conditions.

Thousands of trainees and students were already residing in the GDR prior to the 1980 intergovernmental agreement with the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV). On 7 August 1976, a group of 65 Vietnamese youths began an apprenticeship at the publicly owned Robur bus and truck plant in Zittau, the GDR’s leading commercial vehicle company. Ministry for State Security (Stasi) employees

At a meeting on 23 August 1976 the Vietnamese trainees decided to strike. The next morning, they all refused breakfast.

The Stasi employees worked quickly to gather information about Vietnamese trainees in other companies, discovering there had also been disruption elsewhere: wall newspapers had been defaced, a group of trainees stood up and left in the middle of an event with representatives from the Soviet youth organization, and one company reported damage to machines and defective products allegedly caused by trainees.

The authorities were particularly concerned by the fact that the trainees had formed a close network: “It has been assessed by the comrades of the State Secretariat that the individual groups of Vietnamese trainees have established an advanced level of contact with each other and that there is an excellent flow of information about embassy measures regarding individuals, incidents etc., despite great spatial distances.” There is no mention of attempts at reconciliation or mediation in the Stasi reports.

In the Robur plant, things had come to a head. Trainees were refusing meals, and trainee management first threatened and then succeeded in forcing them to work without food.

Imposing Order and Discipline

The next day, German company officials declared that workers who continued to strike would be reported to the Vietnamese embassy and deported. The Stasi report notes that “cooperation with the embassy of the SRV may be considered good. The justified requests of the GDR to impose discipline and order have been acknowledged and implemented using the embassy’s resources.” Out of 65 trainees, 40 subsequently resumed work. Ten trainees wanted to break the hunger strike, but were prevented from doing so at mealtimes by the others.

In the meantime, the State Secretariat for Vocational Training was working together with Vietnamese diplomats to compile a list with the names of 14 trainees across various companies who were considered to be particularly mutinous. The repatriation of these individuals began before the ultimatum to resume work in Zittau. Without further commentary, the Stasi reported that: “In the night between 25 and 25 August, a suicide attempt was made by a Vietnamese trainee who belongs to the group of 14 trainees mentioned. However, his life is not in danger”. There is no indication as to whether the trainee was sent back to Vietnam (BStU 1).

My Workplace – My Battlefield for Peace! 1 May 1989 motto of the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany

Labour disputes were not expected in publicly owned enterprises in the GDR. Strikes were seen as an expression of political opposition and were de facto prohibited.

Nevertheless, migrant workers continued to opt for this form of industrial action. When the State Secretariat for Labour and Wages reported that a total of 6,000 contract workers had taken part in different strikes in 1975, a range of measures to improve working conditions came into force the following year (Roesler 2012). In 1976, 600 Algerian workers in eight companies downed tools again. Their protests focused on the lack of skills training that they had received, and their use as auxiliary staff in a manner that violated the terms of their contracts. As a result, the agreement signed two years previously between Algeria and the GDR was amended in favour of the Algerian employees (Schulz 2011).

Some of the governments of the migrants’ home countries did not support their citizens, as attested by this report on Cuban workers:

“On 17 November 1983, 9 workers at the VEB brown coal plant in Borna did not turn up for work because the distance to the bus stop (200m) was too far to walk in cold weather. In coordination with Cuban authorities, five workers were immediately deported. From the Cuban side it was reiterated that employment in Borna was a political assignment. Workers hoping to extort concessions through a refusal to work were classed as ‘traitors’ to the political cause.” (BArch 1)

Strike!

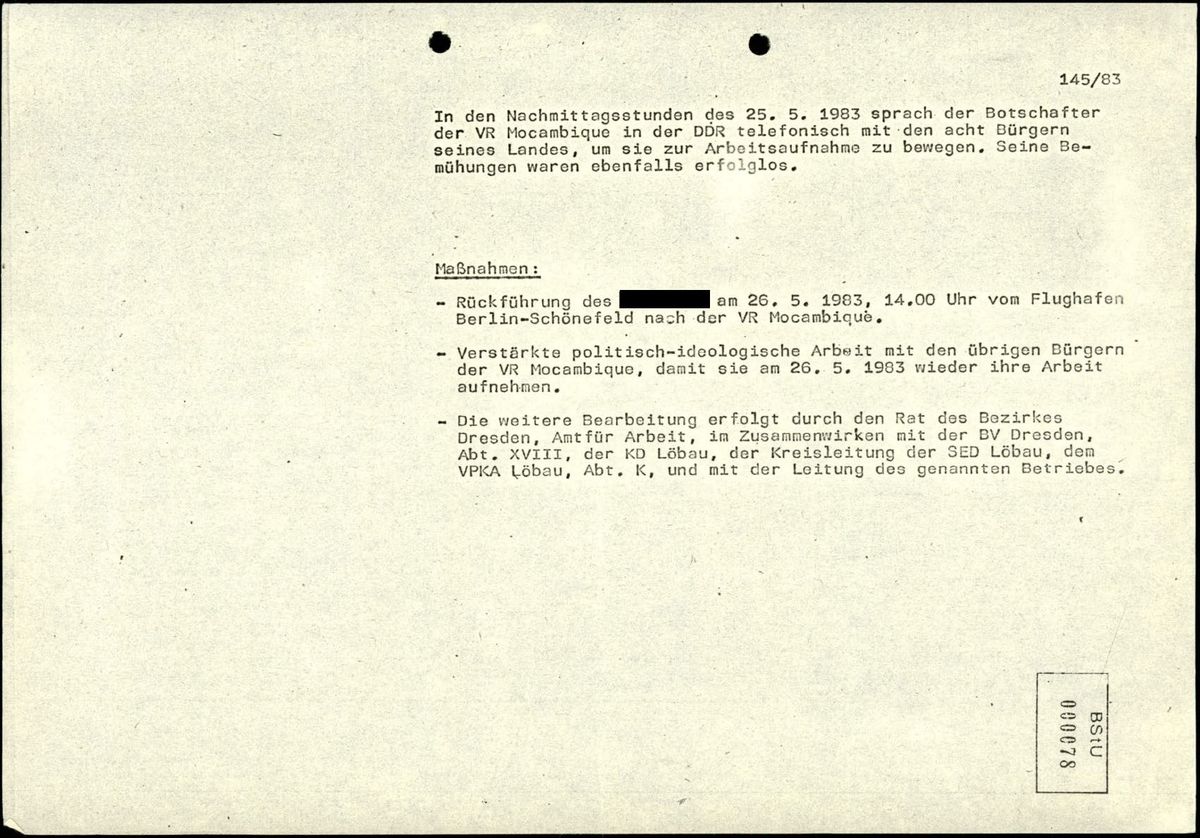

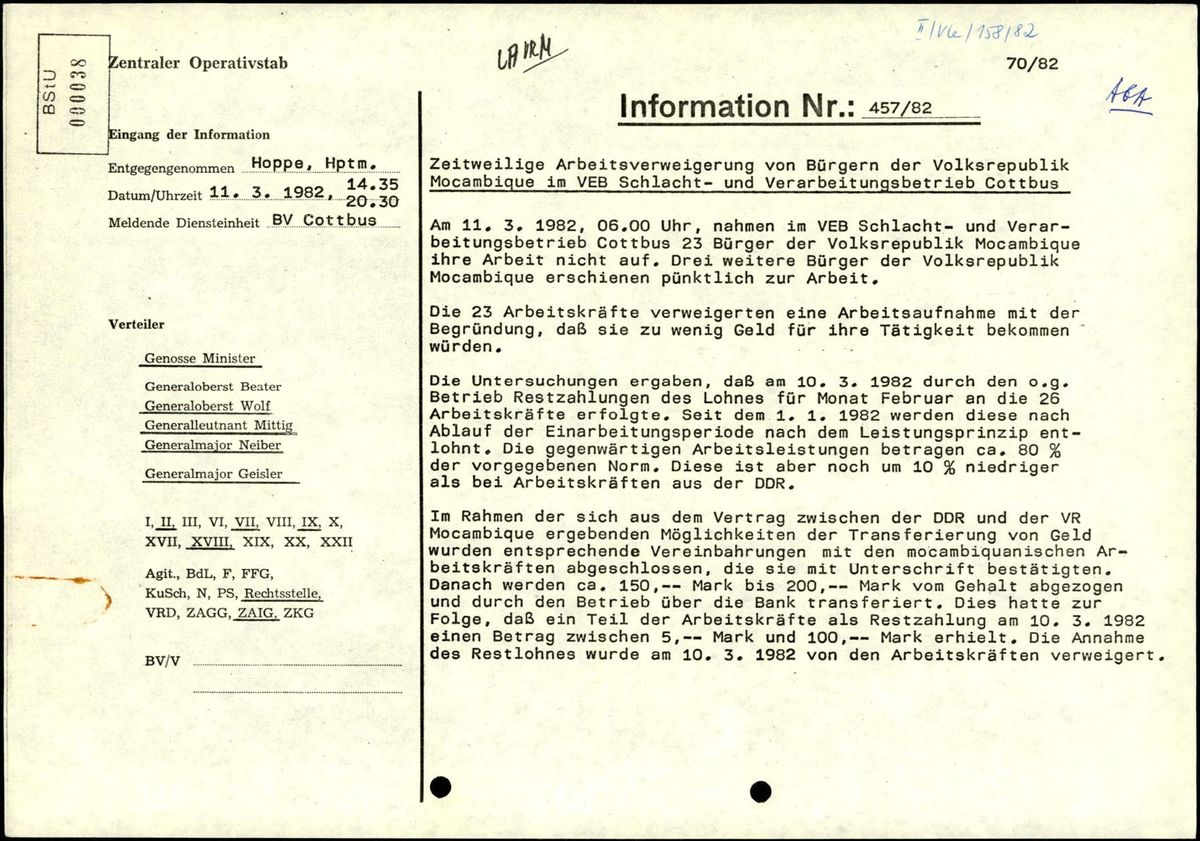

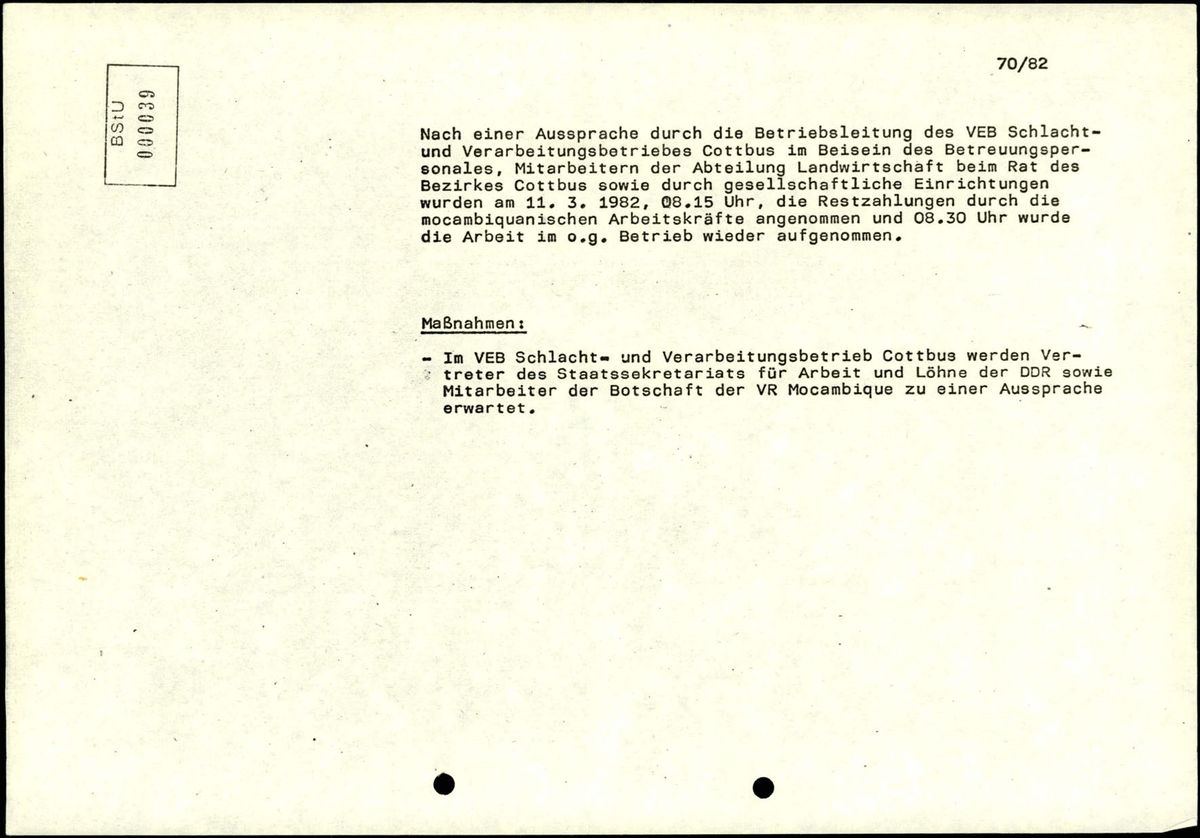

All forms of work stoppage were registered by the Stasi as “noteworthy incidents”. If foreign workers went on strike to assert their interests, publicly owned enterprises would respond immediately, notifying the State Secretariat for Labour and Wages as well as diplomatic representatives of the striking workers’ home country. The disputes were mostly related to wage demands. The following are two examples of strikes documented by the Stasi:

In the VEB Cottbus slaughterhouse and meat processing plant at 06:30am on 11 March 1982, 23 Mozambican contract workers stopped work because they were being paid too little money.

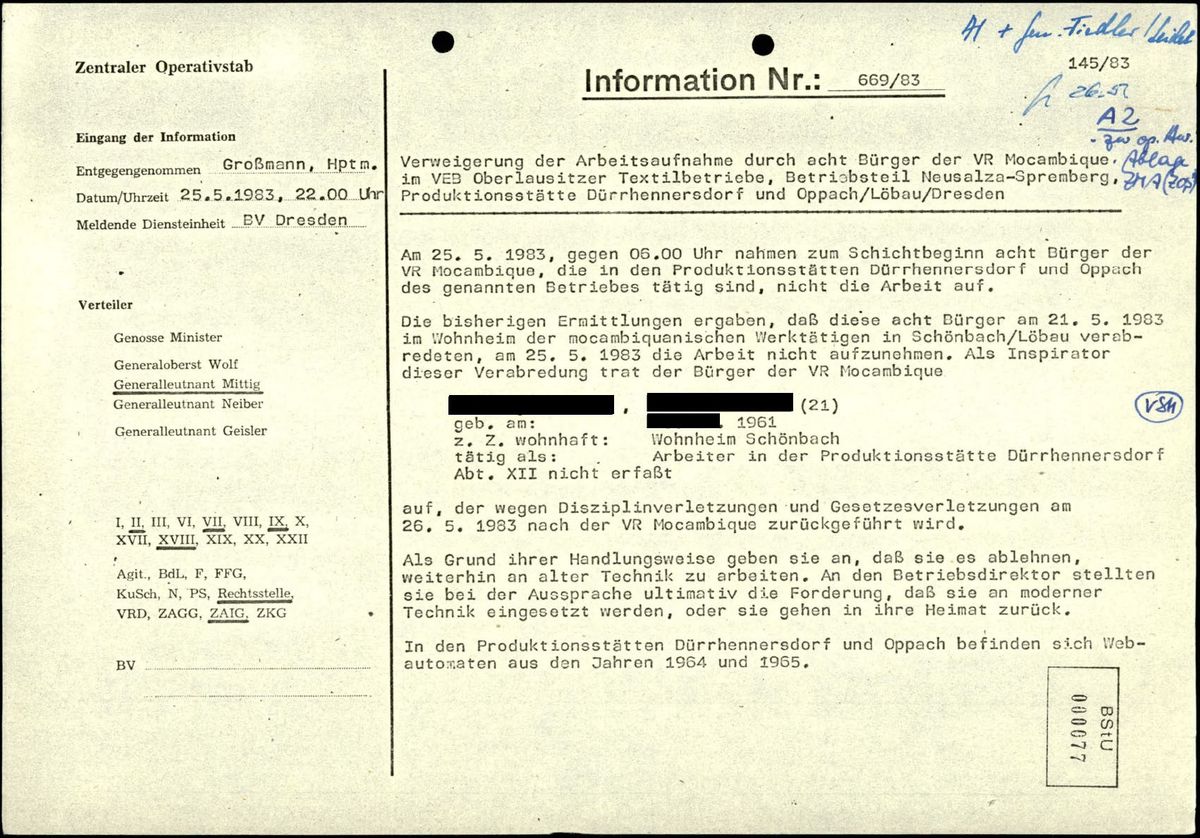

In the VEB Oberlausitzer textile company on 25 May 1983, eight Mozambican workers downed tools. They refused to continue working with outdated equipment and requested to work with modern machines. The Stasi identified the “instigator” of the strike, who was promptly “sent back” to Mozambique.

Equal Rights, Equal Obligations

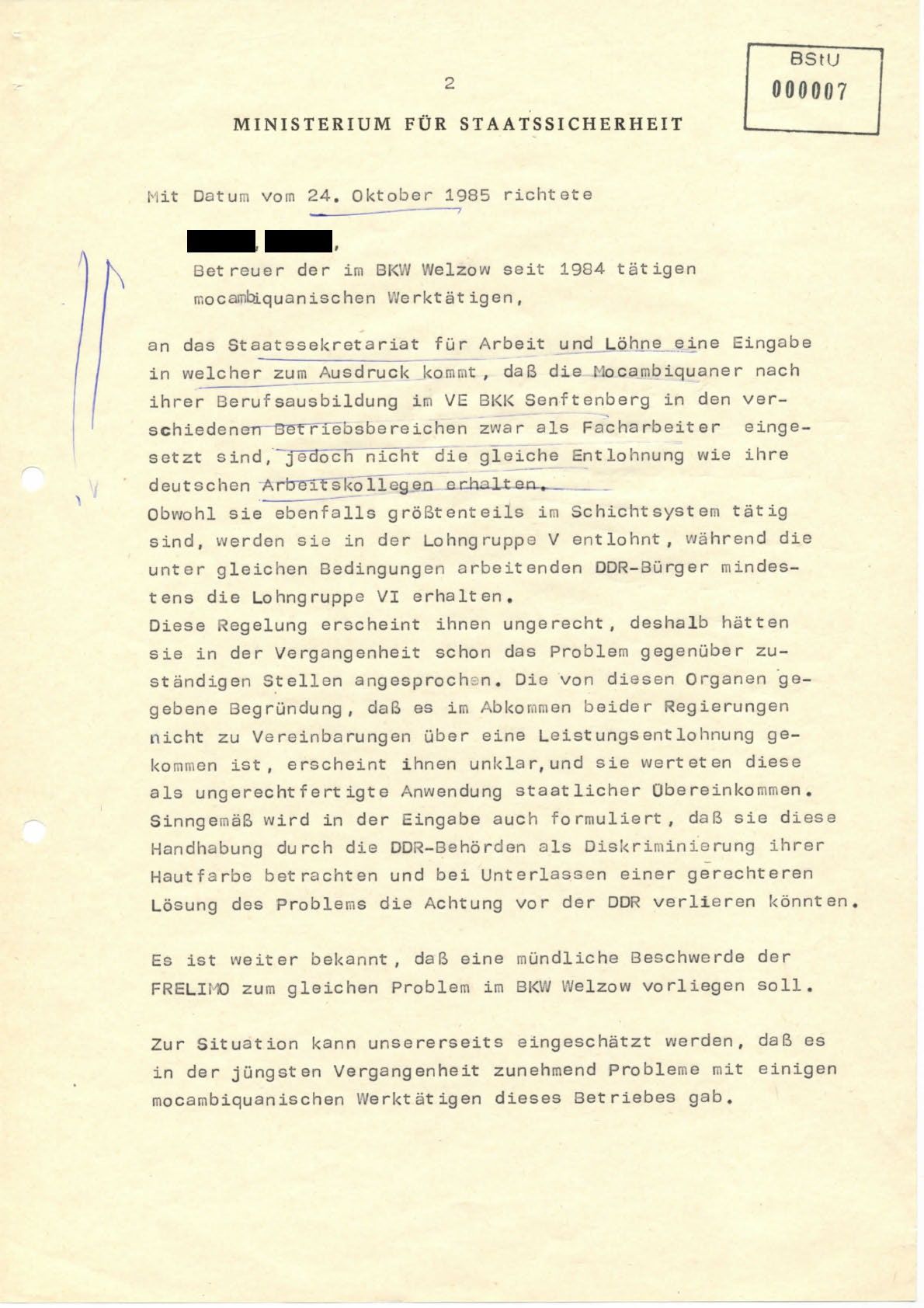

According to intergovernmental agreements, foreign contract workers had the same rights as German workers. In reality, however, they were frequently given physically demanding or dirty jobs for lower pay (Roesler 2012).

Wage Disputes

A recurrent reason for strikes and work stoppages was the payment of wages. Contract workers’ salaries were subject to a wide range of levies. In addition to union dues and social security, their rent and catering costs were directly withheld by the companies they worked for. The level of salary was linked to performance, and sometimes bonuses were paid out. Part of a worker’s salary had to be transferred directly to their home country. A significant part of the salary was the separation allowance of four marks per day. This was the same amount stipulated in the first basic agreement for the transfer of workers, made in 1967 between the GDR and Hungary. All foreign workers were entitled to a separation allowance, but following work stoppages by Algerian employees, it had been turned into a means of discipline: payment of the allowance was bound to compliance with disciplinary regulations at work. This was expressly stipulated in intergovernmental agreements with Mozambique and Vietnam.

The complex array of deductions from wages was not transparent, not always correct, and often incomprehensible to the workers.

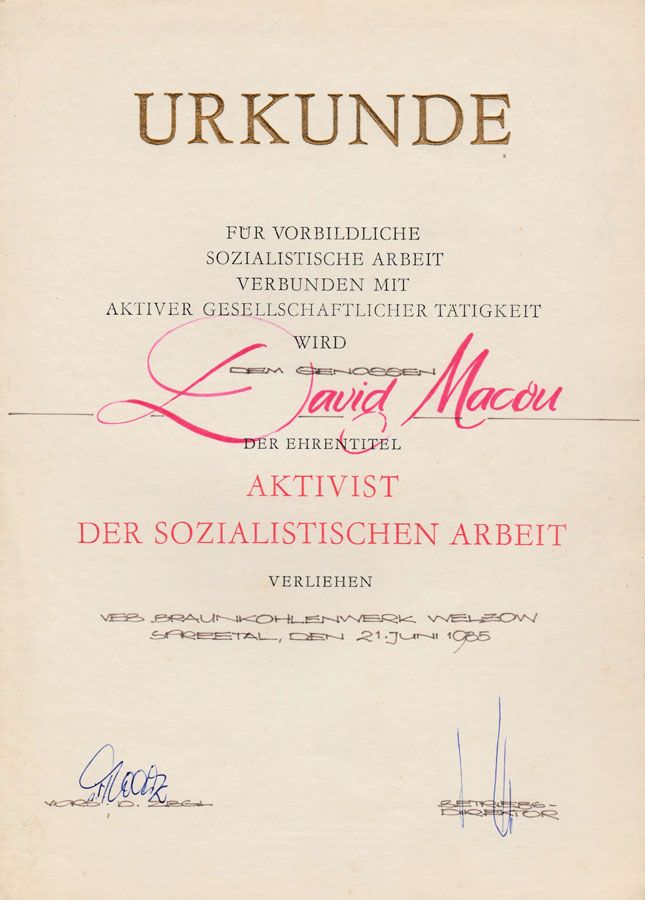

The first Mozambican contract workers arrived in Hoyerswerda, Saxony in 1979. Among them was David Macou. These young men were assigned to different brown coal mines in the Lusatian region. David Macou worked in the Welzow brown coal plant, where he trained as a welder.

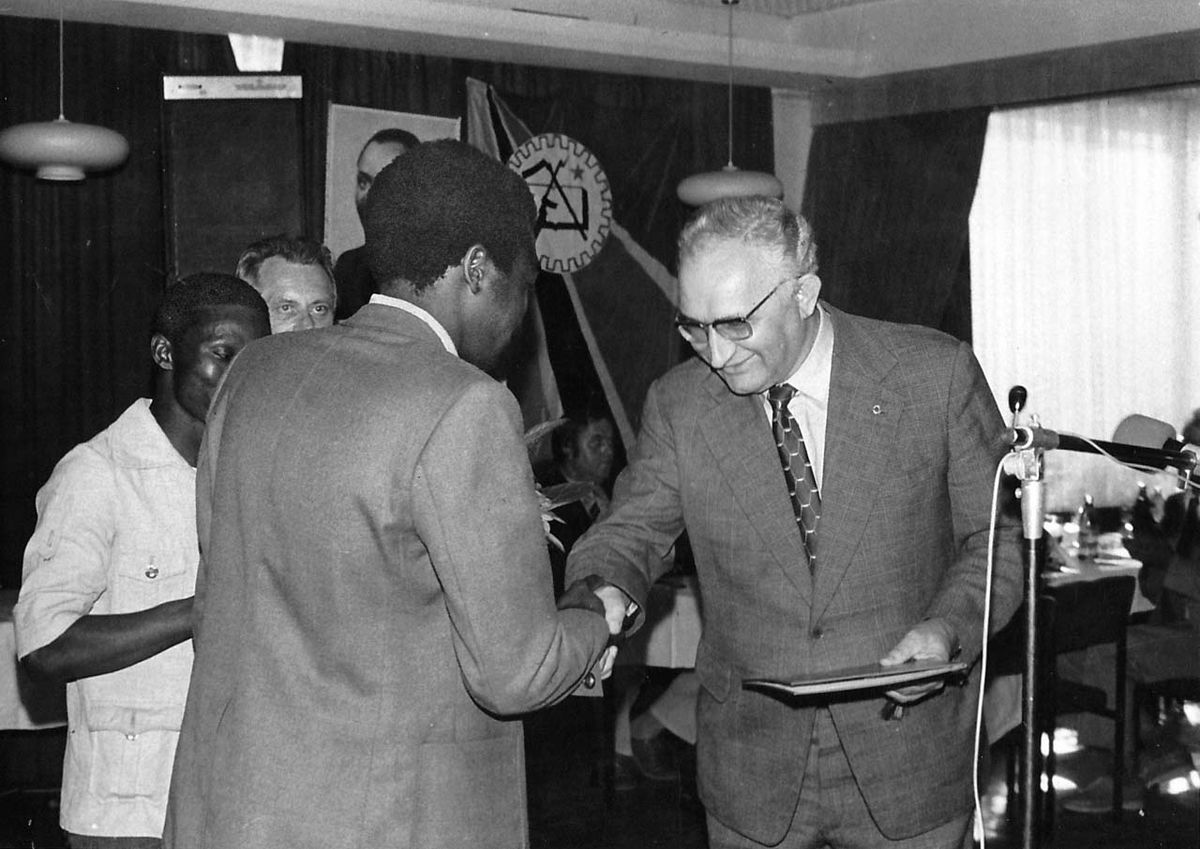

Mozambican diplomatic representatives named David Macou as their group leader. Active in FRELIMO (Frente de Libertação de Moçambique), he enjoyed the trust of both the East German and Mozambican authorities. Group leaders acted as intermediaries between company management, Mozambican representatives, and the contract workers. Where problems arose, these were to be solved by the group leader—talks were seldom conducted with the affected person. David Macou passed his skilled worker examinations with distinction. His contract was extended, with his official status now that of a skilled worker.

»My salary was the same as that of a trainee

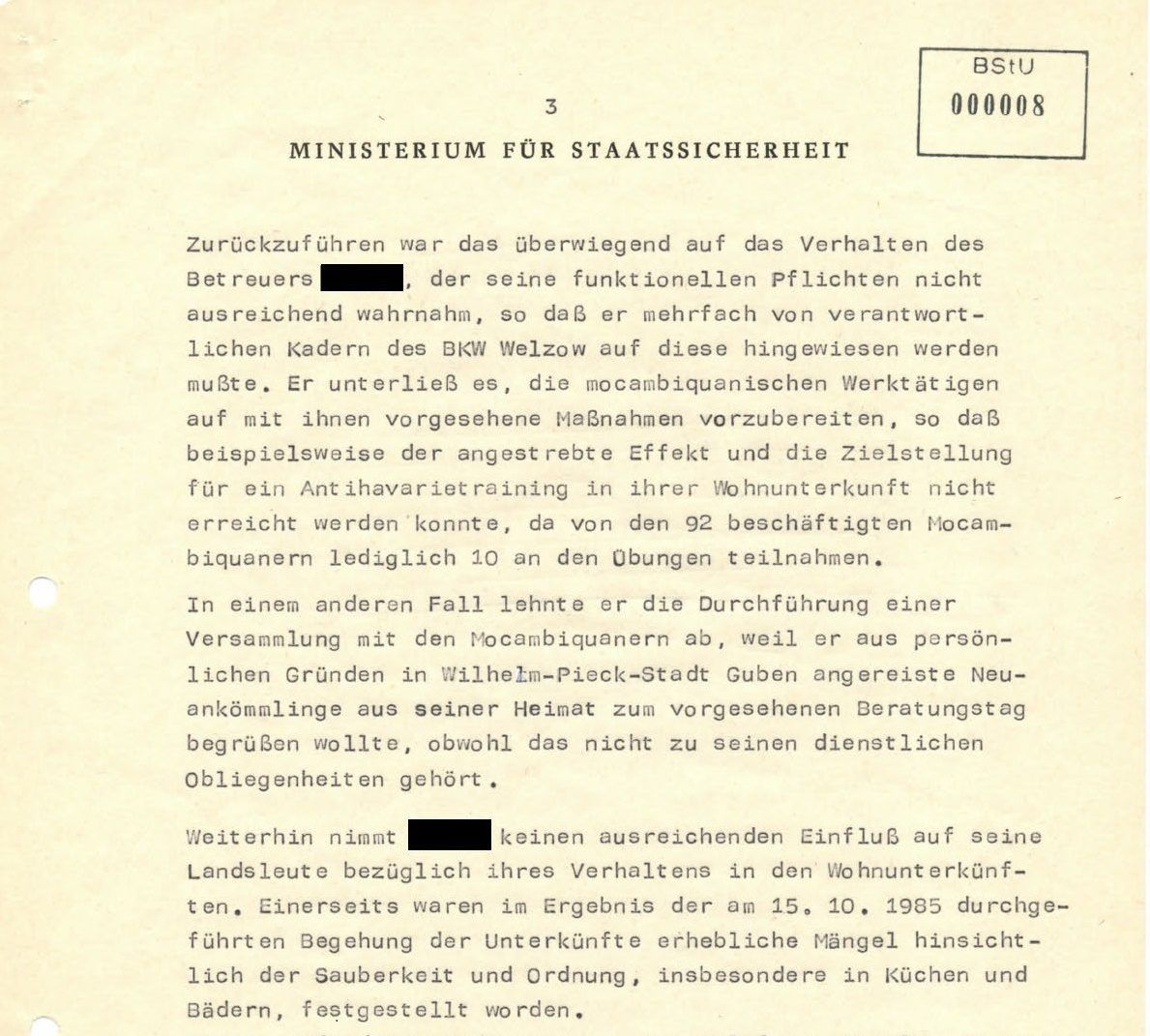

After acquiring his skilled worker’s certificate and attending the ensuing meetings, David Macou was placed on a higher salary level. But now the Stasi had him in their sights. In their strictly confidential reports, they vilified him personally and called his integrity into question. His performance at work was not mentioned; rather, he was accused of having too little influence over the private behaviour of other Mozambican workers.

In addition to the Stasi, a number of other institutions recorded and evaluated the behaviour of migrants living in East Germany through reports and notes. This clearly indicates that state control and interference deeply encroached upon the private lives of migrants. The same was true for students and political emigrants in the GDR.