Living in hostels was not unusual in the GDR. There were too few apartments in general, and these were allocated by government agencies. Students, trainees, and workers were all housed in hostels. But the rules in accommodation for foreign workers were especially strict, and the migrants were monitored closely. Visitors always had to report to the porter and their presence was recorded. Note was made of who was leaving the lodgings as well as the times they left and returned. Given these conditions, the migrants mostly spent their time with each other.

East German companies had to apply to obtain contract workers and in addition to a work schedule for manufacturing, they had to demonstrate that they were providing accommodation for workers. In rural areas in particular, this was not always easy. In three or four-room apartments, up to four people were living in each room, and from 1980 onwards, each person was allocated five square metres of “personal space” (Mac Con Uladh 2005 b, p. 53). There were communal kitchens for cooking and in some places, caterers would prepare food for all the inhabitants. Workers often had their meals in the work canteen, students ate in the dining hall in college. The customs, cultural preferences, or religious requirements of migrants were rarely taken into account when it came to the meals provided.

»I thought, what’s this black bread stuff?

Annual Supervision Reports

Companies were required to provide the State Secretariat for Labour and Wages with annual supervision reports in relation to the deployment of the contract workers. The reports had to provide information on various aspects relating to the migrant workers, such as their level of qualification, work discipline, health status, political views, as well as their conduct outside of work. These reports read very differently. Many are matter of fact and simply describe problems in production. But there are also abundant examples of reports that clearly demonstrate German company employees acting in a paternalistic way towards the foreign workers. The need to educate the migrants is frequently mentioned, but their self-will is also noted.

The Case of Görlsdorf

25 Mozambican workers were employed in a publicly owned livestock cooperative in Görlsdorf and lived directly on the factory grounds. One highly detailed report from 1982 by the people in charge there describes problems related to the employees’ free time.

“In our opinion, the employees are not spending their wages in the right manner (…). Our suggestions to this end are rarely followed (…). On the other hand, there is a lack of essential items such as sports clothing and lunchboxes (…).

We have found that the longer their stay, the more the employees from Mozambique turn to alcohol. As a result, discos regularly (…) end in fights. We know that the Mozambican employees are not always the instigators here. Nevertheless, we have been considering ways in which we could introduce more meaningful leisure time activities (…).”

(BArch 3)

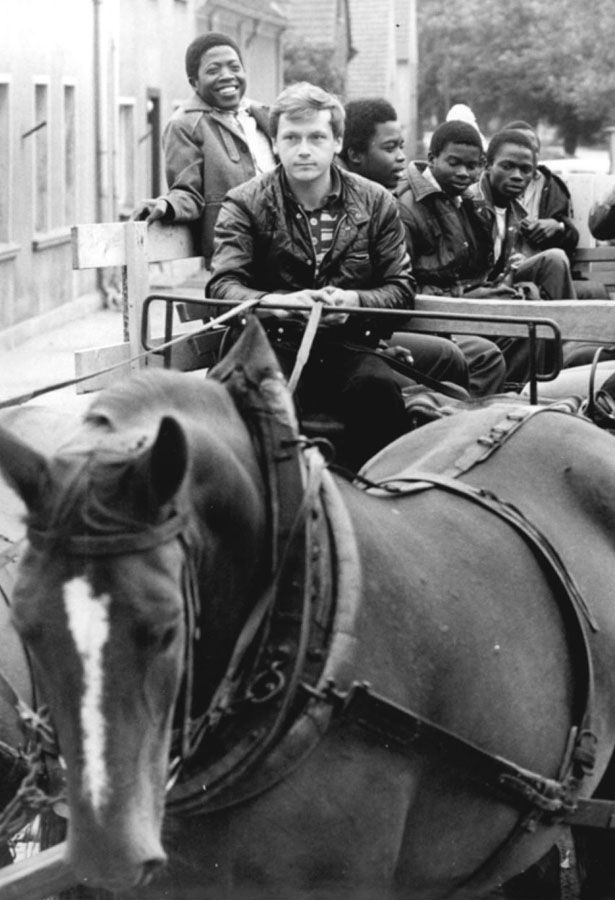

Görlsdorf in the Media

The text from the state news agency ADN that accompanied this photo was as follows: “A ride on a horse-drawn cart can be enjoyed by anyone––just like these young men from Mozambique. Together with their GDR friends, they have been getting to know the Luckau area that is set to be their home for four years. They are being trained as skilled workers in the publicly owned livestock cooperative in Görlsdorf, where they will be employed in one of the two 2000-head dairies there. The young men from far-off Africa have a good relationship with the inhabitants of Görlsdorf. (Note to editors: Photos from the Friendship day organized by the Free German Youth movement and the Mozambican Youth Organization, between 3–10 July 1981).”

More Meaningful Leisure Time Activities

The supervision report for the company continues as follows:

“Since September 1981, two hours of sport lessons have been organized weekly for the employees. Here we should note that most Mozambican employees are not taking this seriously. Our request that they purchase sports clothing has not been heeded. Aside from organized sports, the employees enjoy playing football (…). The organized collaboration with our local equestrian club has not been made use of either.”

The report ends with these words:

“We have also ascertained that our Mozambican employees need a lot more education on these matters, since their current attitude is: we do our work and in our free time we need to sleep or go for a walk.”

Werktätige der sozialistischen Landwirtschaft! Kämpft um hohe Erträge auf dem Feld und im Stall!“Workers in socialist agriculture! Strive for high yields on field and farmyard!“ 1 May 1975 motto of the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED)

In Control of Their Own Leisure Time

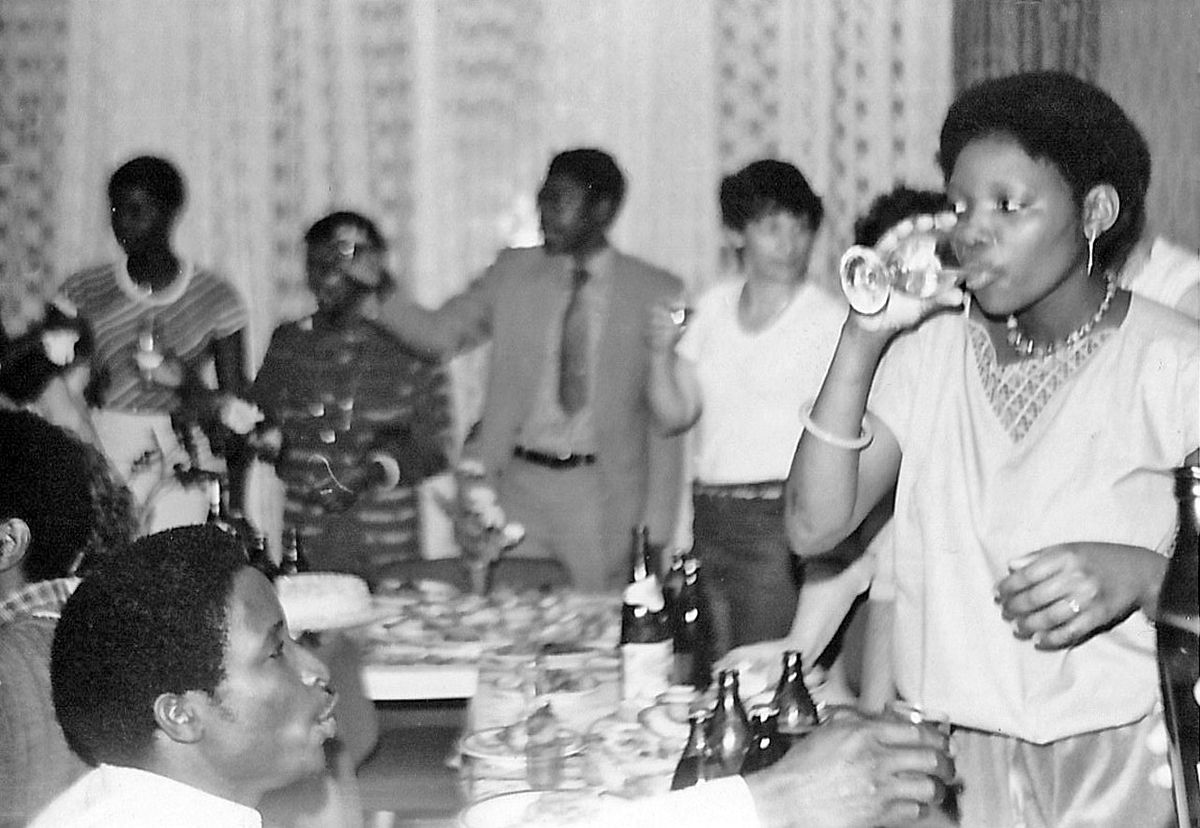

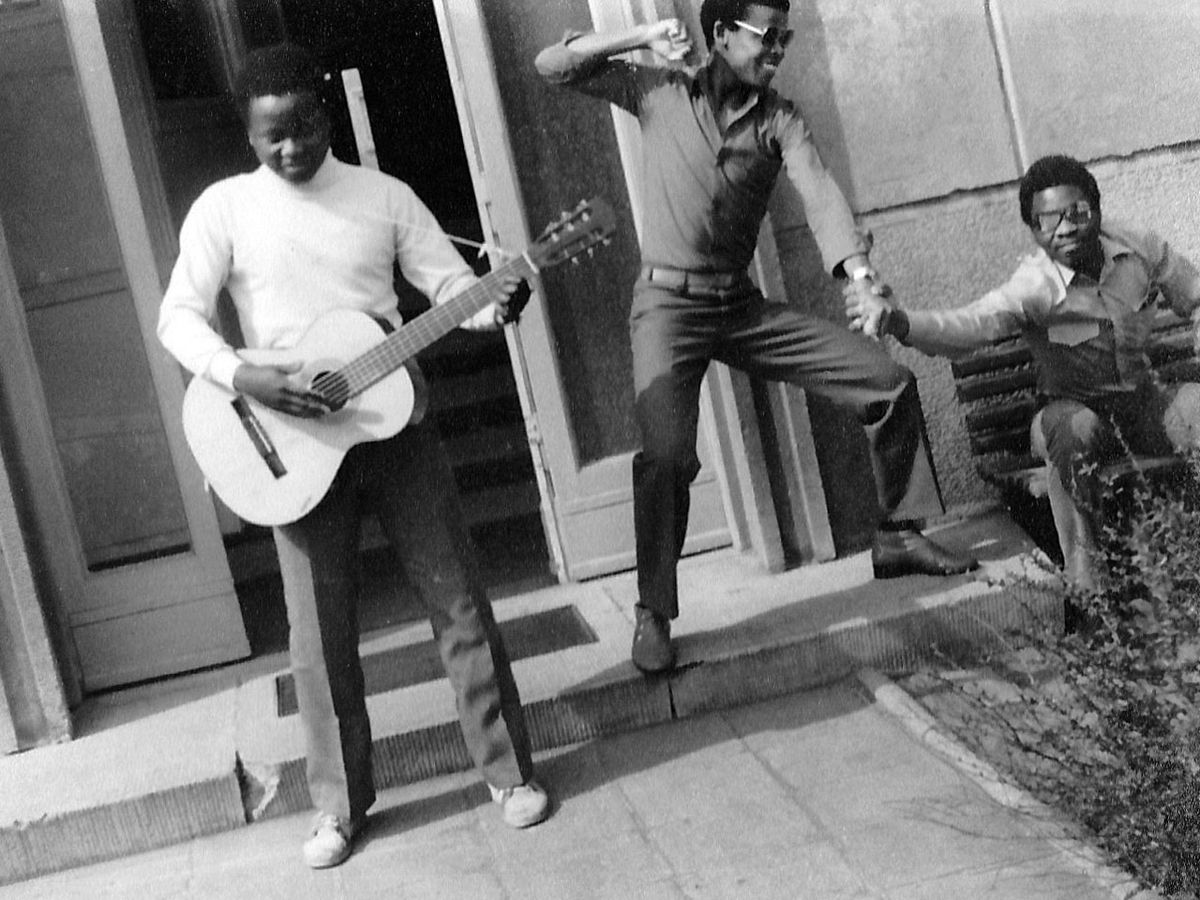

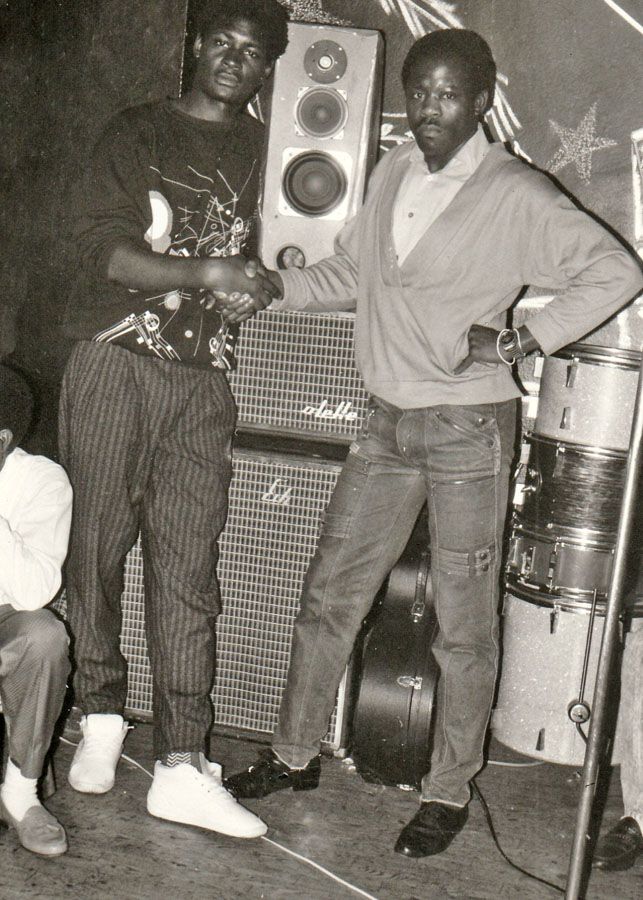

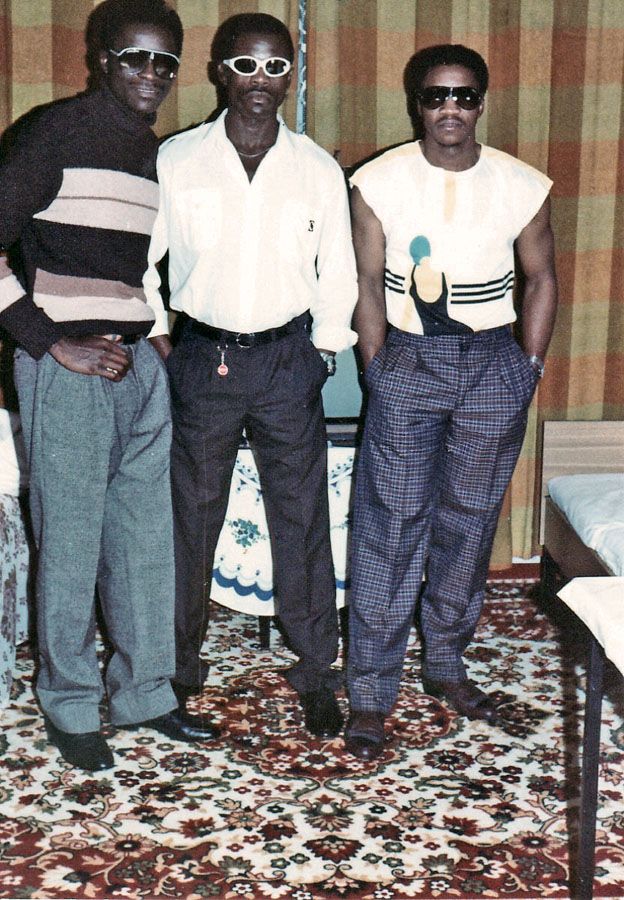

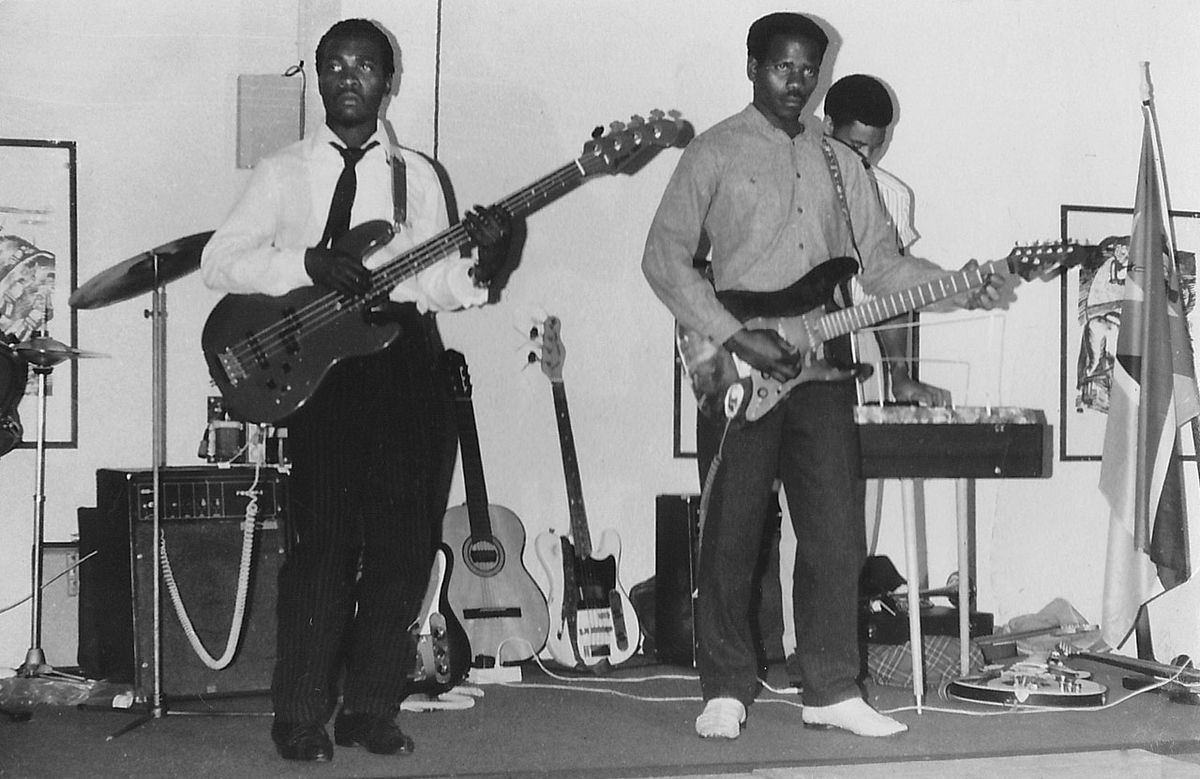

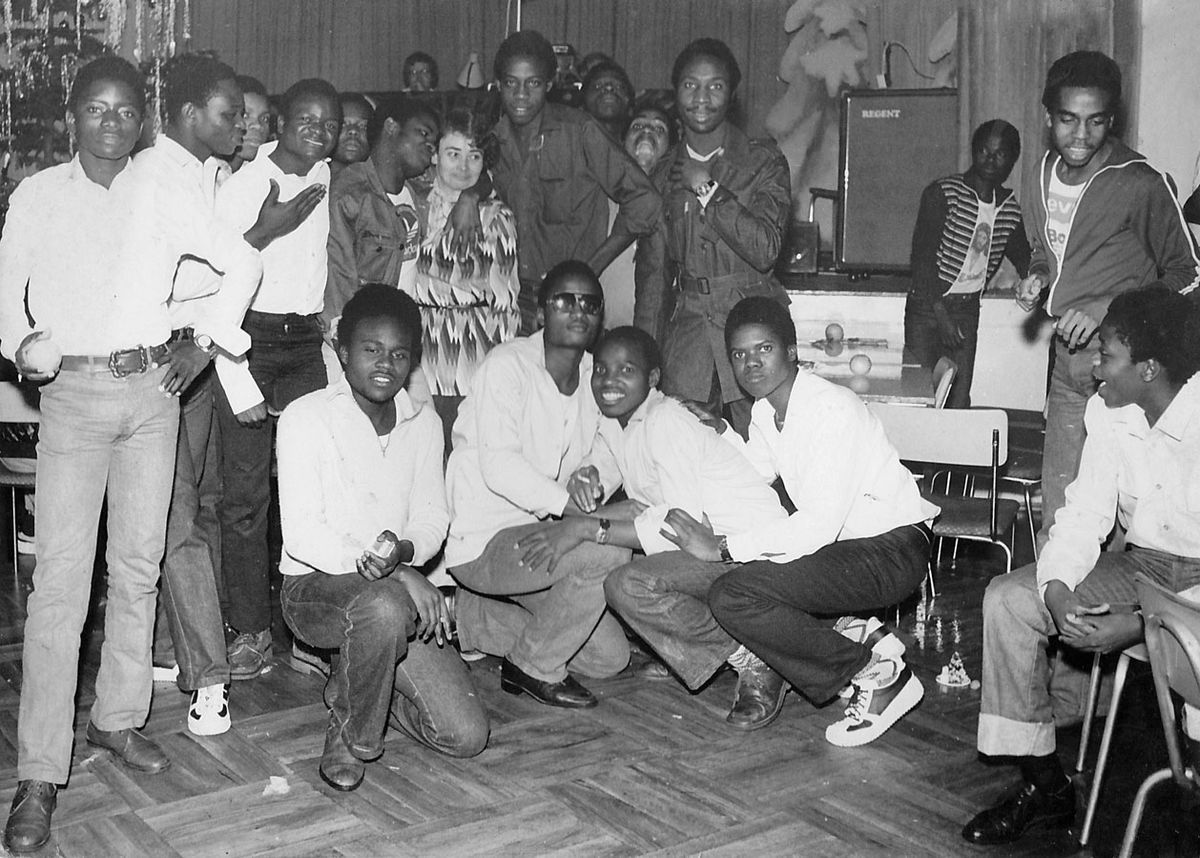

The GDR and diplomatic representatives from the migrants’ countries of origin could not dictate how the migrants spent their free time, however, and attempts to regiment this often came up short. Lots of social activities were organized: the migrants held parties in communal living areas, went to the local discos, took trips to other towns and cities, played sports, or cooked together in their accommodation. Women usually had less freedom than men in terms of how they spent their free time.

»Music in the GDR was weird, too

On weekends, many of the contract workers went to visit people in other cities in the GDR. As the workers had had no influence over their employment location, friends or relatives often lived far away. In the case of Vietnamese workers, even married couples could sometimes be separated and sent to work in different locations. These weekend trips were a thorn in the companies’ side. Regular complaints appeared in the supervisory reports about these trips as well as the sick leave that occasionally resulted from the workers’ being away. (BArch 2)

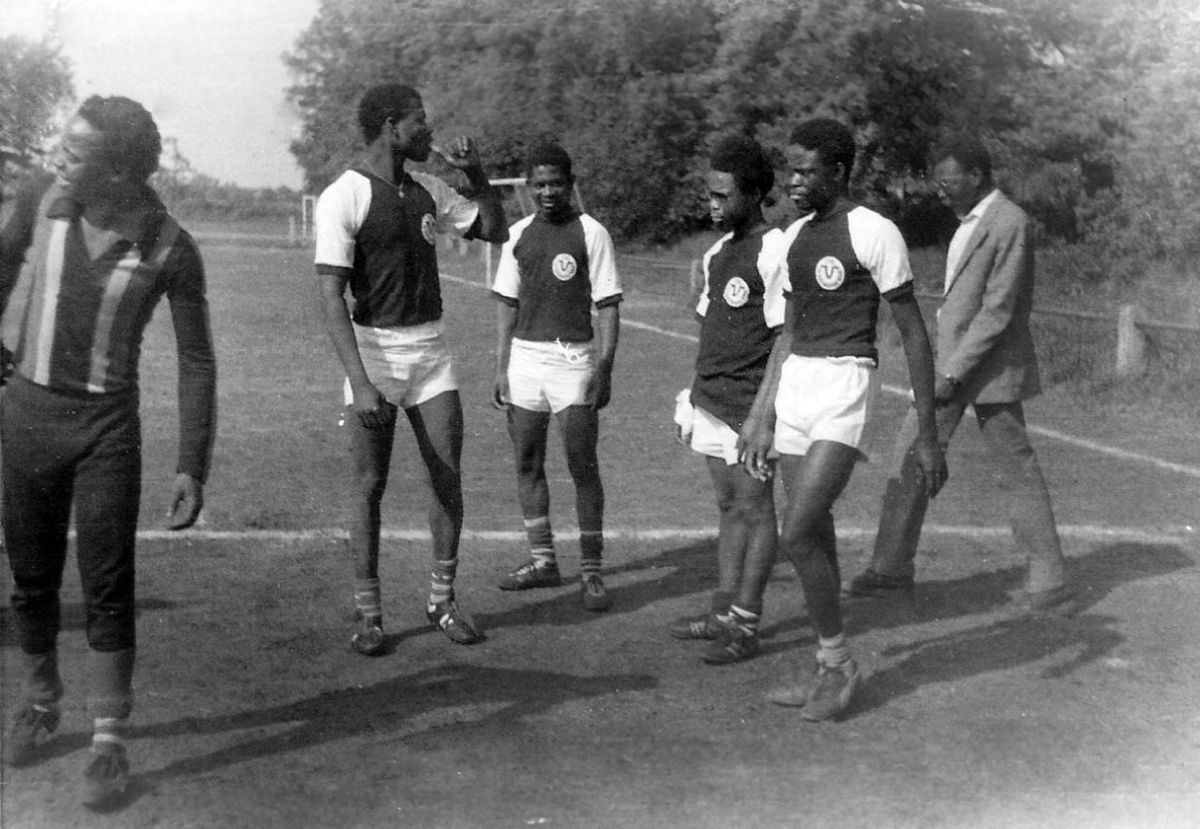

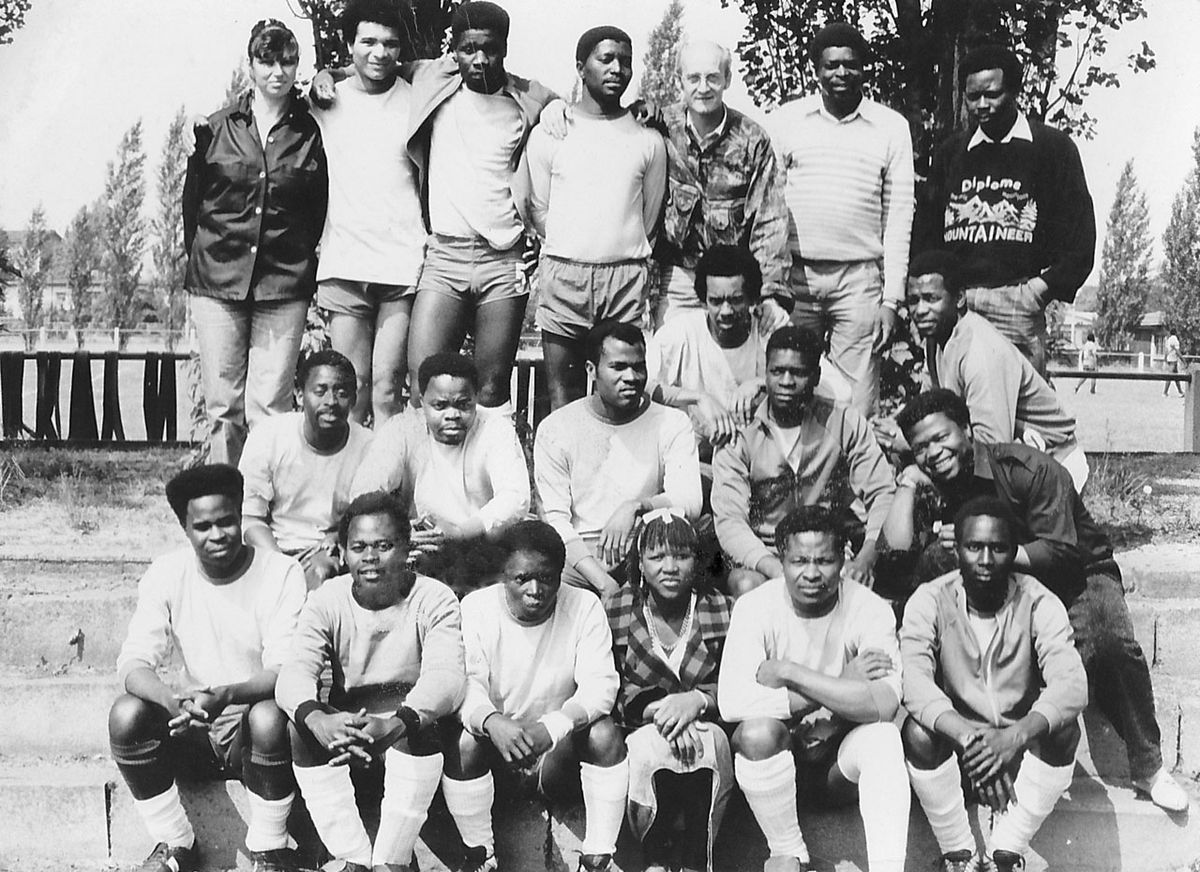

»We went away on trips a lot and even ran our own discos

Another reason for weekend trips away was football tournaments and other sports events, which took place all over the country. Sport played an important role in the GDR, and migrant workers also took part in competitions at the company, district, or regional level. In many companies, migrant workers formed their own football teams, usually based on their country of origin. According to gymnastics and sports federation rules, independent clubs were not allowed to be formed––only teams of foreign players within a club were permitted. As a result, teams of Mozambican, Vietnamese, and Cuban players competed in tournaments. However, their participation was restricted to district level (Mac Con Uladh 2005, p. 58)

From the Disco to the Hospital

When migrant workers stepped outside of their own communities to go to discos or bars and restaurants they were often turned away, or suffered racial hostility. It was not uncommon for these outings to end in violent confrontations. Numerous incidents are documented in the files: one example is a “noteworthy incident” that transpired in October 1982 in Orlamünde.

The first report the company director sent to the State Secretariat for Labour and Wages described the incident as follows:

Ten Mozambican migrant workers wanted to visit a pub. The customers who were already gathered there refused them entry, telling them a private function was taking place. The Mozambicans protested and, as described in a report filed the day after the incident, “caused a disturbance”.

The company director outlined how the situation escalated:

“the mozambican citizens were forced out of the pub. nine of the mozambican employees crossed a level crossing directly in front of the bar. the gates came down on the level crossing and one mozambican citizen had to wait on the side next to the bar. he was beaten there by four german citizens.”

“he got away and tried to escape over the tracks. in doing so he was struck by a train and thrown off the tracks”

“this mozambican citizen is now being treated in hospital in jena. he is badly injured. the local police administration in poessneck transferred the investigation to the local police administration in jena and to the transport police” (BArch 4)

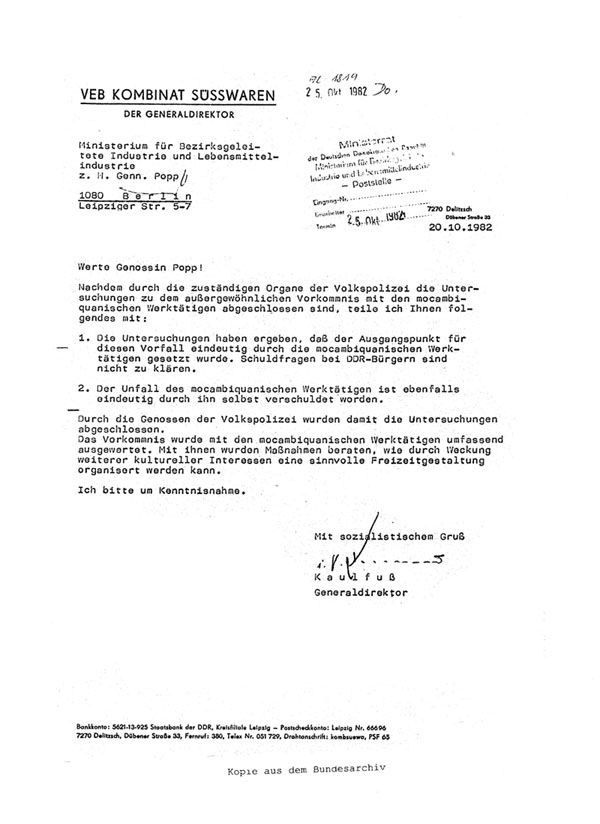

“The question of whether GDR citizens were liable is unresolved”

Three weeks later, the people’s police resolved the case. The company director shared the police investigation results in a new report, in which the German citizens were absolved of any blame.

No further information was provided about the health of Afonso M., the man who had been injured.

The document states: “1. The investigation has revealed that the incident was clearly provoked by the Mozambican workers. German citizens have been absolved of blame.

2. The accident involving the Mozambican worker was clearly caused by the worker himself.”

The investigation was thus concluded. The Mozambican workers were advised to organize “culturally appropriate leisure time activities”.

It is highly probably that the injured man was taken care of by the Mozambican group leader, who was responsible for mediating and resolving problems and conflicts as far as possible in the interests of the company.

The Split Loyalties of Group Leaders

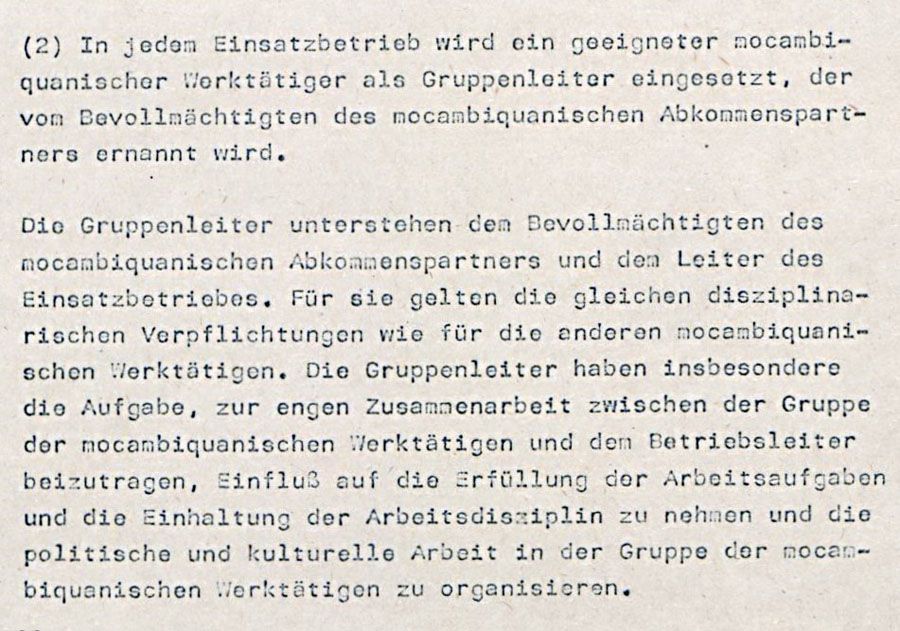

For each group of contract workers, diplomatic representatives from their country of origin appointed group leaders who were responsible for communication between embassy, company, administration, and worker. With this position, both parties benefited from opportunities for influence and control. In most cases, the group leaders were exempted from work so they could carry out their role. They had been selected by diplomatic representatives for their country of origin. The Socialist Republic of Vietnam was particularly strict about assigning the position of group leader to workers who were reliable and exhibited absolute loyalty to the party. The tasks assigned to Mozambican group leaders are described in the agreement below:

The document states: “(2) A suitable Mozambican worker is to be employed in each company as group leader; this group leader will be appointed by the authorised representative of the Mozambican party to the agreement.

Group leaders shall be subordinate to the authorised representative of the Mozambican party to the agreement and to the company manager. They will be subject to the same disciplinary requirements as other Mozambican workers. In particular, group leaders are responsible for promoting close cooperation between the Mozambican workers as a group and the company manager, for exerting influence on the fulfilment of work tasks and on maintaining work discipline, and for organizing political and cultural activities within the group of Mozambican workers.”

»We were young and free

David Macou held the role of group leader in the VEB Welzow brown coal plant. In 1985, Ibraimo Alberto became group leader for new arrivals from Mozambique to the VEB Stralau glassworks in Berlin. Here they talk about their experiences and reflect on the conflicting nature of the role of group leader, but also on its possibilities for change.

Supporting Family Back Home

Many of the Vietnamese contract workers continued to work after the working day had ended. They were under huge pressure: 12 percent of their gross income had to be transferred to the Vietnamese state for the purposes of rebuilding the country. They were also expected to send back goods to support their families: in fact, this had been set out in the intergovernmental agreement between the GDR and Vietnam. Each Vietnamese contract worker was allowed to send a package valued at 100 marks twelve times a year to Vietnam and could send a parcel duty-free with no limit in value six times a year. The biggest effort of all was filling the crate that each worker was permitted to take with them if they travelled to Vietnam for home leave and at the end of their period of residence: one to two cubic metres with a maximum weight of one tonne was allowed. (Dennis 2005, p. 21)

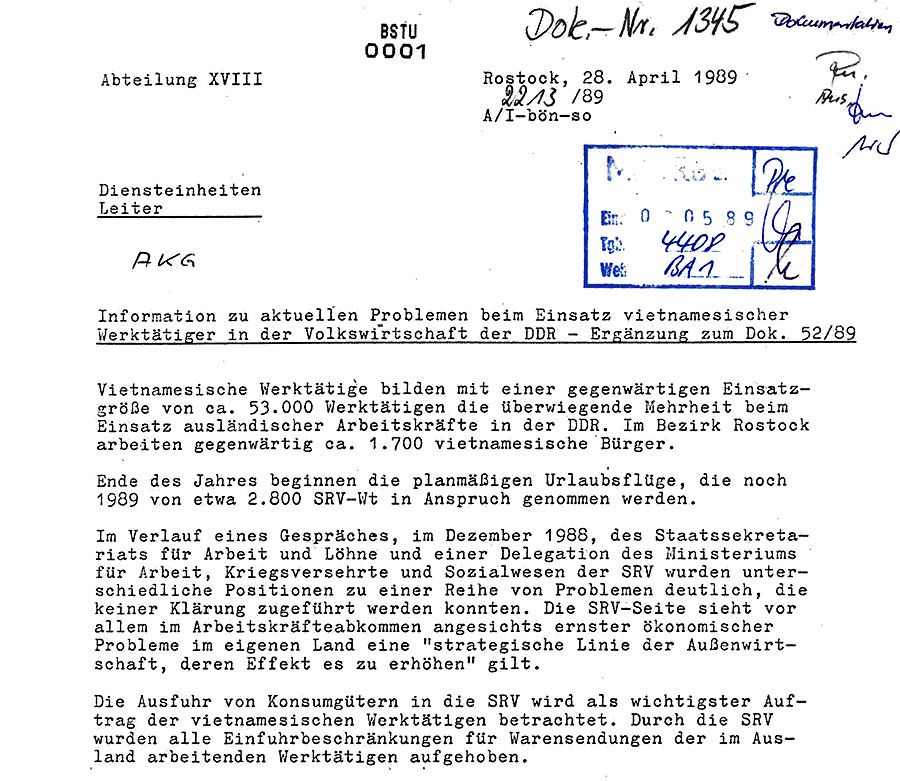

Family members were not the only ones counting on the shipments. The Vietnamese government saw these deliveries of goods as an essential reason for deploying workers to Germany. The type of goods and the quantity allowed in crates was tightly controlled. A Stasi report records a meeting between the State Secretariat for Labour and Wages and a delegation from the Ministry of Labour, War Invalids and Social Affairs of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

The salary of the workers was not high enough to buy the goods that were required back in Vietnam. Some began to sew clothes, in particular jeans, which they would then sell on an informal and private basis to mostly German customers. In this way, they were meeting a need that was not fulfilled by the planned economy of the GDR. Their activity did not contravene any laws, and since it was tolerated by the Vietnamese leadership and the East German authorities, workshops sprang up in the migrants’ accommodation for making jeans, shirts and other items of clothing. This developed into a broad, well-organized network in which a degree of corruption benefited various parties.

»People were mostly ordering jeans

Sourcing fabric and utensils for sewing and goods for the crates to Vietnam was not easy in the GDR, where there was an economy of scarcity. Certain food items such as rice were only available in limited quantities, and demand was never met. East German citizens frequently saw Vietnamese contract workers as competition for consumer goods that were in short supply, and were hostile to them. There were rumours that the Vietnamese workers were earning money from West Germany and were able to enrich themselves individually. They were often the targets of insults and hatred.

In the late 1980s, the situation worsened for migrants in the GDR, as economic and social conditions deteriorated. The plan to alleviate these problems through the mass employment of migrants resulted in fierce aggression towards migrants from GDR citizens. Even Stasi reports outlined the racism the migrants faced.

The report laments that an agreement was not reached. For the GDR government, the sending of goods to Vietnam posed a significant problem in light of the economy of scarcity in the GDR. However, the Vietnamese government representatives made it plain in the meeting that: “the export of consumer goods to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV) is viewed as the Vietnamese workers’ main task. The SRV has lifted all import restrictions on goods sent by workers abroad.”

The document states: “The emerging hostility to foreigners, a lack of mass political work on the part of the GDR population, inadequate leisure time provision by companies and by state and social bodies, and undue pressure on infrastructure that triggered negative reactions among the local population were, as early as 1987, cause for the State Secretariat for Labour and Wages (as the responsible centralized state body) to introduce appropriate measures, the force of which has apparently not yet been fully realized. (Resolution of the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the SED dated 8 July 1987 on “Measures to safeguard the new entry of 4,500 Mozambican workers and their employment in the socialist companies of the GDR in 1988”.)”

A significantly larger number of male migrants than women lived and worked in the GDR, where gender also played an important role in everyday life.