Residency for migrants was not secure during the GDR period, either. Students had to leave the country if their academic achievements were inadequate (see “Study and Political Exile”). Chilean emigrants were deported from the GDR if they, as described in a Stasi report, “could not become accustomed to social conditions in the GDR” or if – and here the report uses Nazi terminology – “criminal and work-shy elements” were observed (BStU ZAIG 4097, p.8).

Grounds for Expulsion

Time and again, Mozambican contract workers had to return to their countries of origin ahead of schedule. According to the agreement between the GDR and Mozambique, any crimes committed in the GDR would result in the termination of the work contract and a premature return to Mozambique. The same applied if a migrant worker “violated socialist work discipline in a serious manner” or was “absent from work for more than three months due to illness”.

Records from this period document numerous repatriation requests. The following are some examples.

A Mozambican contract worker named Armando J. was employed in VEB Baumwollspinnerei Mittweida. He was deported on 5 April 1987. According to the company, the reasons for deportation were that he did not comply with supervisor directions, was absent from work for several days without an excuse, did not observe house rules, and “played a negative role within the Mozambican group”.

Ana M., also from Mozambique, worked in VEB Oberlausitzer Textilbetriebe. Her repatriation request accused her of not complying with schedule, refusing to work with all machines, working slowly on purpose, and not fulfilling the obligations of the intergovernmental agreement. On 1 November 1987, she was deported.

In addition to multiple repatriation requests for pregnant women, the files include many examples of people whose ability to work was limited due to long-term illness, traumatic war experiences, or other psychological problems. These workers were also deported to their home countries, some of which were still in a state of civil war.

The Berlin to Maputo flight, 20 September 1987

At least four contract workers were sent back to Mozambique on a flight on 20 September 1987. They were:

Veronika C., a worker at VEB Feinspinnerei Erzgebirge, Venusberg in the Ore Mountain region and Emilda M. from VEB Oberlausitzer Textilbetriebe, both of whom were pregnant.

Laurinda M., also employed at VEB Oberlausitzer Textilbetriebe, had twice evaded repatriation on the grounds of pregnancy. In August 1987, her child did not survive birth. The company requested her repatriation due to “lack of discipline” and wrote: “We insist upon immediate repatriation, as this behaviour can no longer be tolerated and it has moreover affected discipline in the workers’ accommodation. In our view, it is essential that Mozambican officials are involved in the repatriation, as it is to be anticipated that this individual will refuse to travel again.”

Antonio M., who worked at VEB Reh-Kinderkleidung Erfurt, was being repatriated due to mental health problems. The company wrote:

“The doctor treating this Mozambican worker informs us that he has threatened suicide if he is returned to his home country. For this reason, we request that an escort accompanies him to Mozambique.” (All quotes from BArch 9.)

»I was not accepted as a human being

Migrants suffered racist insults and hostility in everyday life too. The contract workers, in particular, were constantly reporting incidents ranging from verbal abuse to threats of violence from GDR citizens. In their annual assessment of foreign workers in the GDR from an operational policy perspective, the Ministry of State Security (Stasi) noted that “incidents with Mozambican workers in September 1987 confirm that this group is subject to an increasing level of provocation by GDR citizens” (BStU 5).

Nguyen Do Thinh was on the receiving end of discriminatory remarks at his workplace, and Ibraimo Alberto was subject to abuse and threats from the audience when taking part in boxing matches.

Compulsory Transfer of Wages

Some bilateral agreements stipulated a “transfer of wages” for contract workers. Vietnamese workers had to send 15 percent of their net income to Vietnam (Gruner-Domic 1997, p. 26); this money was claimed for “post-war reconstruction” efforts. Cubans and Angolans had to transfer 25 percent of their salary back to their home countries.

Of all the migrants, Mozambican workers were the worst off in terms of compulsory wage transfer. They were only entitled to a basic income of 350 marks. From net income in excess of this amount, 25 percent was deducted: from 1986, 60 percent was deducted. The workers were promised that the transferred wages would be kept in an account for them in Mozambique, ready for them to use to establish themselves once they returned.

So wie wir heute arbeiten, werden wir morgen leben. “The way we work today defines the way we live tomorrow.” 1 May 1989 motto of the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany

Compulsory wage deductions were not simply accepted by workers and were a constant cause of conflict and strikes. This is described in a 1989 Stasi report entitled “The current situation regarding the deployment of foreign workers in the GDR”.

The document states: “Due to a lack of opportunities for work in their home country, the standard period of stay for work (4 years) in the GDR is extended for the majority of Mozambican workers.

Stipulations by the government of the People’s Republic of Mozambique regarding wage transfer (60% of net monthly income in excess of 350 East German marks) repeatedly triggered work conflicts.”

Repaying National Debt Using Workers’ Wages

Wages withheld from Mozambican workers were not, as promised, transferred to Mozambique. Instead, the money went towards the reduction of Mozambican state debt to the GDR.

“The amounts were deducted directly in the company from net income, transferred to the GDR Ministry of Finance, and given to the Commercial Coordination Department (KoKo) […] The contract workers were not informed of the practice of debt repayment, i.e. that their wages were not transferred to Mozambique, but used to settle debts” (Döring 2019, p. 30).

Many former contract workers from Mozambique are still fighting to be paid their transferred wages.

The Fall of the Wall

At the end of 1989 around 190,000 migrants were living in the GDR. Of these, 90,000 were contract workers, with almost 60,000 from Vietnam (Weiss 2005, p. 8).

As late as 12 October 1989, the Ministerial Council committee of the GDR had agreed upon 6,000 additional Mozambican workers entering the country to work in the socialist companies of the GDR (Lubanda, no date).

The atmosphere in East Germany changed rapidly after the borders were reopened. With the collapse of the GDR economy, mass redundancies were pending. Many German employees viewed the migrants as competition for jobs. “There were strikes and death threats. Along with petitions, there were demands to dismiss workers who had only come to the GDR a few weeks or months beforehand”, writes the former Commissioner for Foreigners Almuth Berger (2005, p. 69). During this period, racist violence increased dramatically. Even before Hoyerswerda in Saxony made international news headlines in 1991, there was an organized attack there on the Mozambican contract workers’ accommodation on 1 May 1990.

»They said they would be back

One year later, the situation in Hoyerswerda escalated yet again. In September 1991, Neo-Nazis and GDR citizens maintained a week-long attack on the workers’ accommodation and on a hostel for refugees, in full view of police. Town and state authorities saw themselves as unable to bring the situation under control. The majority of the Mozambicans were then repatriated to Mozambique ahead of schedule and the refugees were evacuated from the town.

Unemployed and Homeless

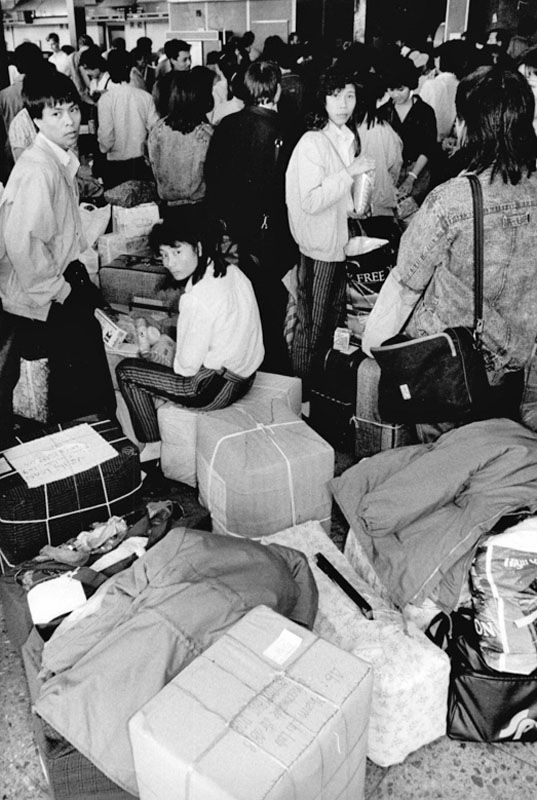

Bilateral agreements with Angola, Mozambique, and Vietnam had been renegotiated by the last GDR government. As a result, a new regulation on labour relations came into force on 13 June 1990, replacing the provisions of former intergovernmental agreements (Elsner/Elsner 1994, pp. 64-70. This meant that companies could now fire contract workers. Losing a job now no longer meant automatic deportation for a worker, but they had to move out of the accommodation that their company had provided. They had to find their own accommodation and a way to earn a living right away. With no connections in German society and a lack of support, many felt they had no possibility of staying. As a special incentive to leave, all contract workers who left the country before their contracts expired were offered 3,000 marks as compensation. The companies organized return flights to their home countries. To ensure that they actually left, the workers often only received the money once they reached the transit area of the airport. The 1991 documentary Bruderland ist abgebrannt by Angelika Nguyen bears impressive witness to the situation of Vietnamese migrants at the time.

»I didn’t know what I was supposed to live on

Nguyen Do Thinh also lost his job, but did not want to return to Vietnam earlier than planned.

Some time later, Nguyen Do Thinh later managed to obtain temporary employment as an advisor and translator for Vietnamese workers at the port of Rostock. His job was to help workers organize their return journey to Vietnam. From 1 January 1991, federal German immigration laws also applied to the former GDR area. Contract workers now received temporary residence permits. This entitled them to reside in Germany until the end of their original work contract. However, they only could receive a work permit if no German or European person could be found for the position they were applying for. In most cases, the only opportunity remaining to migrant workers was to set up a small business and become self-employed in whatever way they could.

It was not until 1997 that former contract workers who had remained in Germany received permanent right of residence. This ruling benefited around 15,000 former contract workers from Vietnam, Mozambique, and Angola, who by this stage were living all around Germany (Berger 1998).

As a rule, foreign students were able to complete their studies in unified Germany, but had to fund their education themselves. Most had been financed in the GDR by a state scholarship, but the scholarship contracts were now no longer valid. From 1 January 1991, state aid for students was only granted in accordance with student loan regulations and eligibility conditions for foreign students. Most GDR scholarship holders did not meet these criteria (Noa, no date).

Routes after the End of the GDR

The people whose stories have featured in this web documentary took different routes. Pham Thi Hoai returned to Vietnam in 1983 after finishing her studies. She returned in 2000 and has lived in Berlin since then. Kadriye Karcı and Alemayehu Gebissa completed their education and stayed in Germany. Kadriye Karcı continues to be politically active, and Alemayehu Gebissa was able to advance his academic career in Rostock. Carlos Medina founded a dedicated international theatre group in Berlin. David Macou and Orquídea Chongo were repatriated to Mozambique. They had no idea about the possibility of remaining in Germany, or about the requirements to do so. David Macou was in the last group of Mozambican workers in Hoyerswerda who had to leave after xenophobic riots there. Nguyen Do Thinh survived an arson attack on Sunflower House in Rostock-Lichtenhagen in 1992. Mai Phuong Kollath, Nguyen Do Thinh, and Ibraimo Alberto married their German partners and were able to retrain for jobs that they had now chosen themselves.