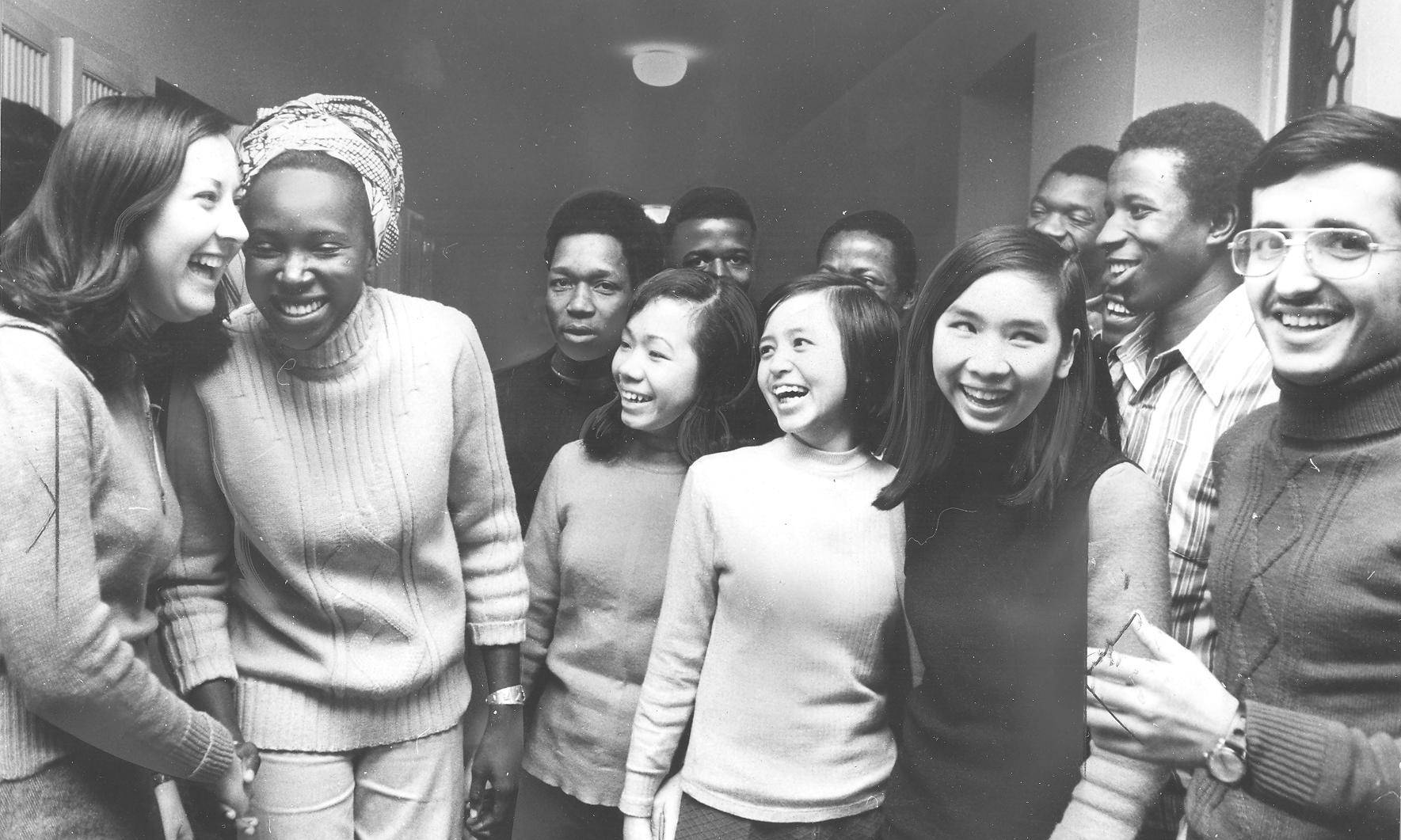

Prospective migrant workers received doctor’s examinations both in their home countries before departure and after their arrival in the GDR, while women also received a gynaecology examination, a demeaning experience described by Mai-Phuong Kollath below. The female migrants were picked up by an interpreter two days after coming to the GDR and brought to the gynaecology clinic without any further explanation. For most of the women, it was their first time at a gynaecologist.

»You have no idea how humiliating it was

The Denial of Pleasure

Despite the fact that Vietnamese contract workers were provided with contraception directly after arrival, there were a huge number of obstacles to forming relationships, such as a lack of opportunities to meet other people, racism, moral attitudes back in Vietnam, and a lack of private space. Their stay in the GDR served national, economic, and political interests, so students were supposed to obtain a good education, enhance the GDR’s international reputation, and contribute to the development of their home country; contract workers were to make up for labour shortages in publicly owned companies in the GDR and support the economies of their own countries; political emigrants were supposed to be able to find refuge and continue their political struggles in exile. Romantic relationships, sexual needs, and pregnancy all ran counter to these interests and were suppressed.

Proletarier aller Länder vereinigt euch!“Workers of the world, unite!” Manifesto of the Communist Party

The economic considerations of their home countries and the GDR determined the lives of migrants and curtailed their personal development. In the companies where they worked they were also subject to gendered stereotypes and expectations, as can be seen in one report regarding Mozambican contract workers in VEB Möbelwerke Eisenberg, dated 13 July 1982:

“For female workers it has been and can be recorded that while they are generally willing to work, they possess a lower level of manual skills, which results in rather superficial and slovenly work results. […] On the other hand, the girls display better work discipline and morale and carry out delegated tasks in a disciplined manner and without complaint.” (BArch 5)

“Mozambican Women’s Day”

A film made by a collective at the VEB brown coal state combine (Kombinat) in Senftenberg (see “Life as a Worker in the GDR”) stressed that working women could receive the same qualifications as men. On Mozambican Women’s Day, they received particular praise, but did not seem to show the anticipated reaction.

No Visits After 10pm

Relationships between migrants and Germans were frowned upon, but they did exist. Living situations made things difficult for couples. Both students and contract workers were housed in shared accommodation and did not have their own rooms. The entrance to the accommodation was usually watched by a porter and house rules forbade visits after 10pm.

»I had to do something!

“Antisocial Individuals and Other Undesirable Elements”

German women who visited contract workers in their lodgings and had relationships with them were repeatedly slandered as “antisocial” in reports by GDR authorities. The head of the department for foreign workers wrote the following to his ministry in 1981:

“Prohibiting entry to the accommodation or other measures will not be effective, since there is no supervision in place, and minors, antisocial individuals, and other undesirable elements who are wanted by state security agencies or who are spreading sexually transmitted diseases are loitering in the hostel. […] I would like to take this opportunity to advise you that ensuring a system of supervision for persons entering and exiting is a basic requirement of all work agreements relating to the employment of foreign workers.” (BArch 6)

Ritualized Solidarity

On 8 March, International Women’s Day, female contract workers received flowers, like all other women in the GDR. But if they became pregnant, the proclaimed equality of intergovernmental agreements came to an end.

Abortion or Deportation

A pregnant contract worker usually had two alternatives: to abort her pregnancy or be returned to their home country. The justification for this was that with the birth of a child, she would no longer be able to participate in production to the same extent as before. The “directive for the enforcement of order in terms of company tasks and local state authorities in the context of the pregnancy of Vietnamese women who temporarily work in the GDR on the basis of bilateral intergovernmental agreements” described what was to be done:

“It must be explained to female foreign workers in a timely and convincing manner that they can only meet the needs of work production and to achieve a qualification at the same time if they avoid pregnancy during their temporary residence for employment in the GDR. Companies are obligated, in cooperation with the healthcare facilities and the cadres of the delegation country, to provide female foreign workers with information regarding options and requirements for contraception, as well as for terminating a pregnancy. They must be informed that pregnancy and the birth of a child will, in general, result in the termination of the legal employment relationship and in their return to their country of origin.” (BStU 3)

A deported pregnant worker could not count on receiving support back home. In the eyes of the state authorities, she had violated the official mission to achieve qualifications in the GDR in order to support the development of her home country. In addition, an unmarried daughter who had been sent back early would be a dishonour for most families on a moral and societal level. Pregnant women were by no means sure of support if they were repatriated.

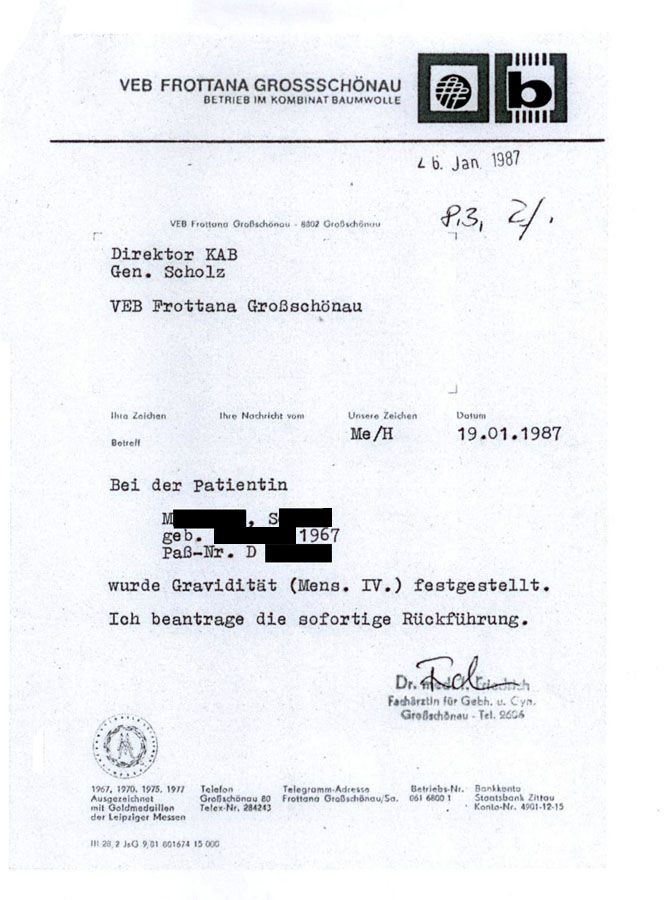

“I Request Immediate Repatriation.”

Rather than doctor-patient confidentiality and medical treatment based on trust, pregnant workers were fearful that their company was working hand in hand with the health authorities to send them back to their home country. Below a gynaecologist requests “the immediate repatriation” of her patient, a 19-year-old from Mozambique – written using stationery from patient’s employer.

Irene M. Fights Repatriation

Contract worker Irene M. arrived in 1981 to work in VEB Getränkekombinat Leipzig. In June 1982, her gynaecologist informed her company that 19-year old Irene was 18 weeks pregnant.

The beverages combine (Kombinat) requested her immediate repatriation to Mozambique. The first attempt to deport Irene failed at Schönefeld Airport in Berlin when she refused to enter the transit area of the airport. She could not be persuaded by either a chaperone for the beverages combine or a Mozambican representative.

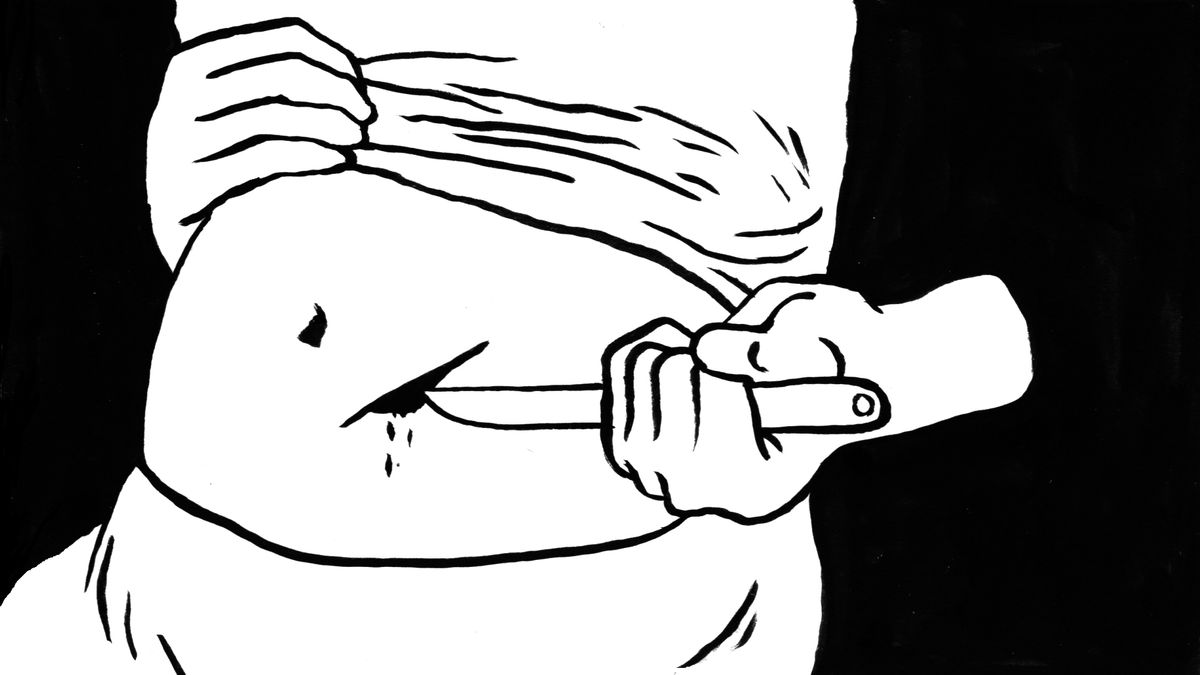

On the return journey from the airport to Leipzig, Irene promised the representative form the Mozambican embassy that she would fly back to Mozambique in a week’s time. Two days later, Irene disappeared from her accommodation, but there was no escape from the beverages combine and she was soon found in another division in VEB Sachsenbräu. When she was about to be brought to Schönefeld Airport to board the flight she agreed to on 9 July, Irene harmed herself.

“Prior to pickup, she inflicted an injury on her stomach with a knife (the cut was relatively slight, since the knife was taken away from her in time).” (Report by state combine director, BArch 7)

Irene M. doggedly continued to resist her repatriation. The state combine director wrote to his superior, the State Secretariat for Labour and Wages, with the following request: “Given what has happened so far, we kindly ask you to clarify the further course of action to take together with the Mozambican diplomatic representatives. Given Irene’s past behaviour, our staff cannot attempt to bring her to Schönefeld Airport again by train or car”.

The letter from the combine director concluded with this plea. Below, there is a handwritten note: “operation completed on 16.7.82”. (BArch 7)

Marriage Undesirable

Romantic relationships were to be prevented, pregnancies were unwanted, and marriages were obstructed to the greatest possible extent. Both the countries that sent migrants to East Germany and the GDR itself set up considerable bureaucratic obstacles to prevent marriage, which would result in permanent residency in the GDR for a migrant, or in the departure of a GDR citizen. A huge number of documents as well as the approval of the respective authorities of both nations had to be produced. As described by a 1977 research paper from the State Security records office, “priority is given to preventing marriages through operational measures” (in Mac Con Uladh 2005 b, p. 63). Some marriages did take place if couples managed to obtain the necessary marriage documents and the approval of both nations. Couples where one partner who was from an East European country had it easier than those with a partner from Vietnam, Mozambique, or Angola. “It is clear that sub-Saharan workers were most affected by state-level and societal forms of racism” (Mac Con Uladh 2005 b, p. 65).

Marriage was often denied to couples who had children together. Out of desperation, some of these affected persons threatened suicide (see “Study and Political Exile”) to avoid deportation. One GDR citizen who wrote many letters of protest to the Vietnamese embassy regarding the fact that she was not permitted to marry her Vietnamese boyfriend and who “spoke of inhumane behaviour” did not only have her plea fall on deaf ears, but may have experienced some consequences. The Vietnamese diplomatic representative requested GDR consular officials to ensure that the women refrained from sending similar letters in future. The officials promised to examine their request.

The Seemingly Impossible

Mai-Phuong Kollath had a German partner, and they were expecting a baby together. She was facing multiple obstacles: she had to keep her pregnancy secret to avoid being deported, and in order to marry the father of her child, she also had to gain the approval of the Vietnamese authorities, who in turn demanded the consent of her parents. They initially refused – only after her child was born did they finally relent. Even then, there were other obstacles to overcome.

»I had such fear, all of the time

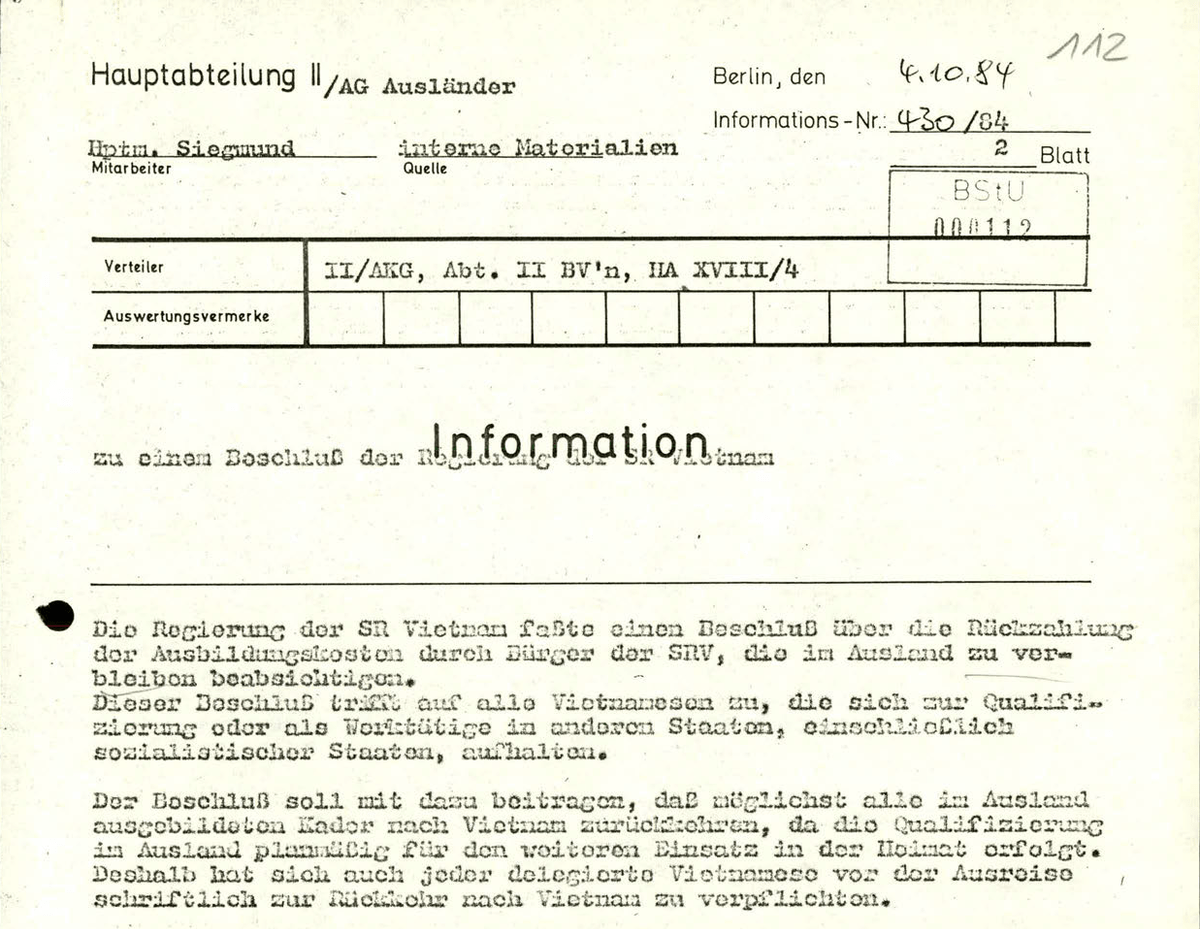

The Vietnamese government demanded a “repayment of education costs”, which could amount up to 12,000 marks, from citizens that they had sent to work in the GDR and who were not planning to return to Vietnam due to their marrying a GDR citizen.

The document states: “The government of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV) passed a resolution requiring the repayment of education costs by SRV citizens who intended to remain abroad.

This resolution applied to all Vietnamese people living in other countries, including socialist countries, for the purposes of educational qualifications or for working.

The purpose of the government’s resolution was to ensure that as many cadres educated abroad as possible returned to Vietnam so that their qualifications could be put to use in their home country as planned. Therefore, before they left the country, each Vietnamese citizen had to sign a declaration that they would return to Vietnam.”

The public statement outlining this rule concludes with the following justification:

“This resolution should serve to make anyone intending to marry a GDR citizen thoroughly reconsider their plans. Experience has shown that differences in mentality, morals and views on family, as well as ties to the home country, often lead to the breakup of these marriages.” (BStU 4)